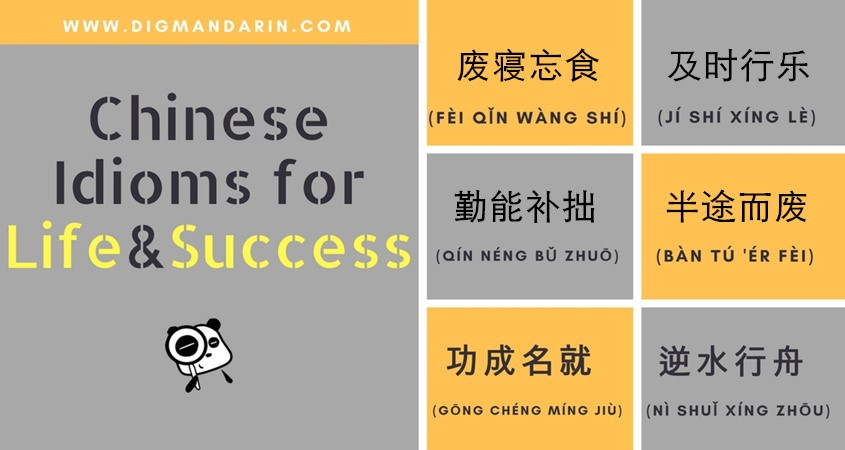

Chinese learners are often told 成语 (chéngyǔ), the four-character idioms, are essential to reach native-like fluency. What are these idioms exactly and how important are they?

What are Chinese idioms or 成语 (chéngyǔ)?

The word 成语 (chéngyǔ) – taken literally – means so much as “already made words”. The typical English translation is Chinese idioms. If we can believe Baidu quoting the Xinhua dictionary, Chinese has more than 30.000 of them. Usually it’s a fixed combination of 4 or sometimes 8 characters that express a profound meaning that derived from ancients myths, fairy tales, Chinese philosophy, poetry and so on. This means that more often than not – to really grasp their meaning – you have to be familiar with the idiom’s story. To figure out how they are used in daily Chinese is even more complicated.

The benefits of learning Chinese idioms or 成语 (chéngyǔ)

Once you move beyond – say – HSK 4 or 5, it grows harder and harder to avoid learning at least a small number of the most basic of Chinese idioms. For native Chinese speakers they are an essential part of the language and culture, but – that being said – it’s not like they drop a chengyu in every second sentence. If you’re reaching for the higher fluency levels, you need a certain degree of passive knowledge of idioms to improve your comprehension of written and spoken Chinese. And – arguably – to take your “cultural literacy” to the next level, although in most cases that won’t be your priority as a learner. When I learned German for example, I read a great deal of Goethe, Schiller, E.T.A. Hoffmann and others, only to find out that “the common German” doesn’t care that much. In terms of improving my communication skills, I could have spent my time far more productively. I think it’s similar with Chinese idioms, that’s why I don’t want to overstate the benefits.

Let me quote John Pasden from Sinosplice instead:

“The fact is that teaching Chinese to foreigners on any large scale is a relatively new thing, and as such, some kinks are still being worked out. Early efforts at teaching foreigners involved a lot of transference of educational methods used on Chinese children. Memorization of Tang dynasty poems, writing out each new character hundreds of times, and memorizing lists of chengyu long before they’re actually useful are time-honored traditions when it comes to teaching Chinese kids their native language. That doesn’t mean these methods are effective for non-Chinese adults learning Chinese, especially when basic communication is the goal.” (https://www.sinosplice.com/life/archives/2013/11/06/the-chengyu-bias)

By the way, Chinese are impressed if non-native speakers use chengyu, but not always for the right reasons. Just think about how you would react if someone who speaks basic English suddenly answers your question by quoting Shakespeare.

Learn Chinese idioms – start from which level?

I just reviewed a new book on getting fluent in Chinese that states you should start speaking from Day One and skip anything non-essential. If that basic assumption is true, where do Chinese idioms fit into this? Just take a quick look at this Chinese idiom story book for children – is it productive to memorize all of them?

Well, unless you’re into the Chinese classics and ancient literature, the answer is: no, probably not. Others may disagree, but I can’t see why you should learn idioms that are mainly part of the written language and have limited usage. Instead, I’d suggest to focus on those idioms you actually encounter on a (more or less) daily basis in the “ordinary language”. A few of them, you typically learn early on, like:

- 马马虎虎 – so-so, not so bad, “horse, horse, tiger, tiger” (learned this one in my first ever Chinese lesson)

- 乱七八糟 – everything in disorder, all sixes and sevens (a common one, often heard)

- 入乡随俗 – when you enter a village, follow the local customs, “when in Rome, do as the Romans do” (learned that one in Chinese class in China)

- 一路平安 – have a safe trip (quite useful)

These four idioms and a few others will get you a long way. So you don’t even have to worry about the when-question that much – you don’t come to them, they’ll come to you. And when they introduce themselves, you’ll see who’s important and who’s merely an infrequent visitor.

Learn Chinese idioms – what if I like to read?

That’s a different question, although the answer doesn’t really change. Once you start reading books like “To Live” or “Game of Thrones” in Chinese, you’ll need to expand your idiom-related vocabulary or will do so automatically in the process of reading. Here are just a few idiom examples from the first chapters of “Game of Thrones”:

- 措手不及 – be caught unprepared

- 大失所望 – to one’s great disappointment

- 视如无睹 – take no notice of what one sees

- 口无遮拦 – have a loose tongue

- 甜言蜜语 – sweet words and honeyed phrases

Actually, I found dozens of them. Sometimes you can guess their meaning, sometimes you can’t. One thing’s for sure: it’s impossible or – let’s say – not very productive to memorize them all.

Learn Chinese idioms – how?

Efficiency is important, so focus on high-frequency idioms only. One thing to notice is that many idioms are used in fairly specific contexts, much more so than in English for example. As a non-native you might think you grasped the meaning and use the chengyu in the right way, unfortunately, it’s not that simple. That’s why it makes sense to learn them in a phrase, so you see how they are used in a sentence and get a sense of the context. I personally haven’t found this kind of learning material, so the best alternative may be to ask a Chinese friend for help.

Commonly used Chinese idioms

If you’re interested in Chinese idioms or – like me – struggling with reading novels and the like, tackling the most frequently used Chinese idioms can be a step forward. However, as far as I can see, there is no consensus on what the “most frequently used” idioms are.

Here’s the source I use a the moment: I started learning the “Essential Idioms” from the vocabulary trainer app Daily Chinese. Apart from a small number of familiar idioms, this is the most challenging set of vocabulary I’ve done so far. Five new idioms a day and retention is not good. Here are the first 35 to give you an impression (and to help my memory):

- 一无所有 – not having anything at all, utterly lacking

- 马马虎虎 – so-so, not so bad, “horse, horse, tiger, tiger”

- 乱七八糟 – everything in disorder, all sixes and sevens

- 半途而废 – to give up halfway

- 理所当然 – as it should be

- 不可思议 – unimaginable

- 七上八下 – a mess, all sixes and sevens

- 九牛一毛 – unimportant, a drop in the ocean, “one hair from nine oxen”

- 顺其自然 – to let nature take its course

- 自由自在 – carefree, leisurely

- 破财免灾 – a financial loss may prevent disaster

- 脱颖而出 – to reveal one’s talents, to rise above others

- 一丝不苟 – not one hair out of place, “not one thread lose”

- 司空见惯 – a commonplace, a common occurrence

- 一鸣惊人 – to set the world on fire, an overnight celebrity

- 一窍不通 – to not know the first thing about, “doesn’t enter a single hole (of one’s head)”

- 谈何容易 – easier said than done

- 一见钟情 – love at first sight

- 爱不释手 – to love something too much to part with it

- 自相矛盾 – to contradict oneself

- 倾盆大雨 – to be overwhelmed with something, a downpour

- 画蛇添足 – to ruin the effect by adding something superfluous, “to draw legs on an snake”

- 守口如瓶 – tight-lipped, “to guard one’s mouth like a closed bottle”

- 塞翁失马 – a blessing in disguise, “the old man lost his horse, but it all turned out for the best”

- 对牛弹琴 – to preach on deaf ears, “to play the lute to a cow”

- 入乡随俗 – when you enter a village, follow the local customs, “when in Rome, do as the Romans do”

- 胸有成竹 – to plan in advance, a card up one’s sleeve

- 淋漓尽致 – vividly and thoroughly, in great detail, “extreme saturation”

- 庸人自扰 – to get upset over nothing, “silly people get their panties in a bunch”

- 绵里藏针 – a wolf in sheep’s clothing, “a needle concealed in silk floss”

- 迫不及待 – to be unable to wait

- 厚此薄彼 – to favor one and discriminate against the other

- 墨守成规 – unwilling to change because of convention

- 随心所欲 – to do as one pleases

- 和蔼和亲 – friendly, pleasant

Conclusion

That’s pretty much it. If you’re main goal is real-life communication, then you shouldn’t prioritize Chinese idioms over high-frequency vocabulary that you can use to have real conversations. But if you are interested, focus on the most common examples like those from the Daily Chinese app I listed above.

PS Here are some articles about chengyu I found useful:

- https://www.hackingchinese.com/learning-the-right-chengyu-the-right-way/: “Ever since I started learning Chinese, I’ve heard people say that if I want to impress native speakers and show that I really know Chinese, the key is to learn chengyu (成语/成語). They are often presented as magic keys not only to the Chinese language, but also to the culture, the people, the philosophy and so on. However, this approach has always irked me. The way chengyu are presented and taught is, in my opinion, flawed. In this article, I will share my own experience of chengyu and how I think they should be approached, both from a student’s and a teacher’s perspective.” (Must-read article on the subject)

- https://www.sinosplice.com/life/archives/2013/11/06/the-chengyu-bias: “So learners, don’t avoid chengyu, but don’t learn chengyu just because they’re chengyu. Don’t give chengyu special treatment when you could be improving your ability to communicate in Chinese. Just think of chengyu as the low frequency words they are, and when you start to encounter them naturally, learn them. When the time comes, you’ll recognize their usefulness in context and will see them more than once.” (amen : )

- https://www.sinosplice.com/life/archives/2005/12/21/my-chengyu-top-ten: “I decided to put together a list of what I consider the “top ten chengyu.” My top ten is determined by what I think a beginner/intermediate student is most likely to hear in conversation in China. I consider these ten the most useful, and the easiest to use.” (A great top 10)

- http://carlgene.com/blog/2010/07/20-actually-useful-chengyu-%E6%88%90%E8%AF%AD/: “Unfortunately, there are few resources – both on the web or in print – that actually tell you which chengyu are worth remembering. This is actually an important question considering that there are tens of thousands of them. Most textbooks simply give you a list of 100 or so and expect you to memorise them all, without actually telling you how they fit into a modern context. The worst are those massive lists you find on the Internet, often sourced from Chinese schools. These are merely lists of idioms that Chinese students are expected to learn at school and, whilst many of them may be well-known, native speakers simply don’t use them as often as you would expect.” (Another list: 20 chengyu that are actually useful and not just random examples)

- https://www.saporedicina.com/english/list-chengyu/: “So below you will find a list of 148 Chengyu and idiomatic phrases that are among the most used in modern China.” (Interesting list, but I’m not sure the “most used” categorization is accurate.)