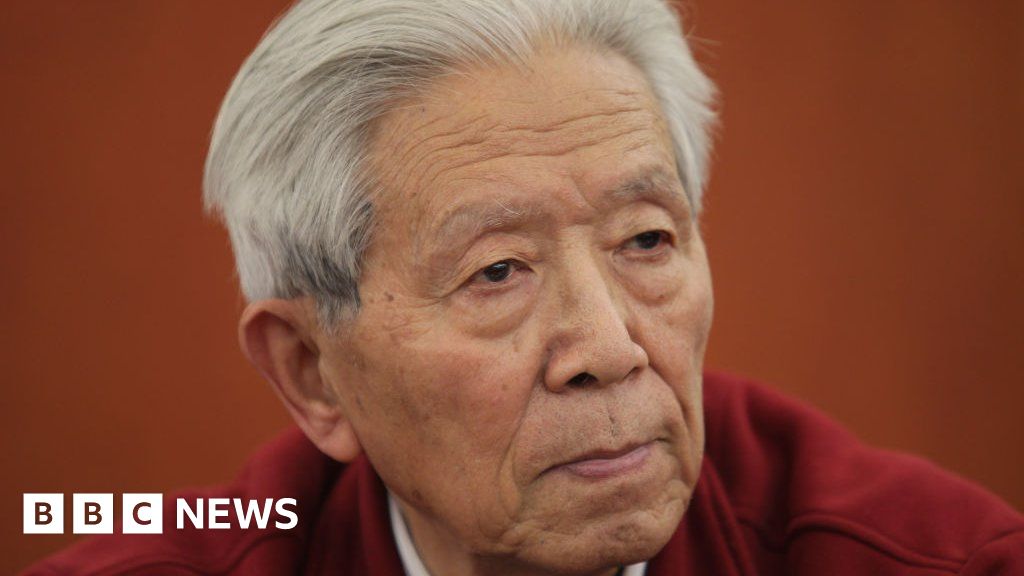

Jiang Yanyong, the military doctor who alerted the world to the real extent of the 2003 SARS outbreak, passed away in Beijing on March 11, 2023. Initially hailed as a national hero, Jiang was later imprisoned and then subject to intermittent surveillance and house arrest after publishing an open letter calling for a reappraisal of the 1989 Tiananmen student movement and the massacre that ended it. The state has continued to suppress memories of Jiang even after his death. Official media made no note of his death and his small funeral was monitored by plainclothes police. Those who attempted to commemorate him online found their works subject to censorship. At least four separate essays on Jiang’s life were removed from WeChat.

The South China Morning Post reported that Jiang died of pneumonia and complications from other illnesses and that he had contracted COVID-19 in January. The New York Times’ Amy Qin wrote an obituary that detailed Jiang’s remarkable life:

Growing up in Shanghai, he resolved to become a doctor after watching his aunt die of tuberculosis. In 1949, the year Mao Zedong’s Communists took power, he enrolled in Yenching University to study medicine and went on to train at Peking Union Medical College, the country’s most prestigious medical school.

Inspired by Norman Bethune, a Canadian doctor who died on the front lines of the Communist resistance to the Japanese occupation in 1939, he enlisted in the People’s Liberation Army and specialized in surgery. In 1957, he was assigned to No. 301 Hospital in Beijing.

[…] But his idealism didn’t last long. In 1966, Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution, the decade-long period of chaos that upended Chinese society. Groups of militant youths known as Red Guards roved the country, determined to root out “class enemies.” Dr. Jiang, whose father had been a banker and whose cousin was an official in the rival Nationalist party in Taiwan, was an easy target.

Branded a counterrevolutionary, he was imprisoned, beaten and later sent to a prison farm for five years in the remote deserts of Qinghai Province in western China, away from his wife and children. After he was politically rehabilitated in the early 1970s, he returned to No. 301 hospital, where he eventually worked his way up to chief of surgery. [Source]

Jiang was semiretired when SARS first broke out. He was spurred to action by an April 3, 2003 press conference in which Health Minister Zhang Wenkang claimed that the outbreak had been “placed under effective control.” Jiang knew that Beijing’s military hospitals were battling a surge of SARS patients and, outraged, he wrote to China Central Television and the Hong Kong-based outlet Phoenix Television to accuse Zhang of lying about the extent of the outbreak. Neither outlet responded. Days later, the letter was leaked to Time. For NPR, Susan Jakes—then a Beijing correspondent for Time and now editor-in-chief at ChinaFile—recalled her first monumental meeting with Jiang and his bravery in uncovering the true extent of Beijing’s SARS outbreak:

A few minutes later, heart racing, I read the single printed page. It was unheard of for a person of Jiang’s stature — as a chief of surgery at his military hospital his rank was equivalent to that of a U.S. major general — to directly contradict China’s most senior leaders, let alone to do with his name and two home telephone numbers emblazoned atop his allegations. I dialed one of them. It took some cajoling but after a few minutes on the phone he agreed to meet me later that afternoon at a hotel near his hospital.

[…] I worried he might not realize that publishing his statement in Time could bring him danger. Confident I had already corroborated most of his claims, I asked him if he wanted to remain anonymous. His refusal was adamant. He was telling the truth. It would be far more credible with his name attached, and he said he was prepared to face the consequences, whatever they might be.

We published that night. By the end of the next day, after Jiang fielded calls from dozens of reporters, the military instructed him to stop talking to foreigners. He called me to tell me this. But the following week, when a World Health Organization SARS inspection team visited Beijing hospitals, he still found a way to pass me information. Both military and civilian hospitals in Beijing had hidden SARS patients from the inspectors. One hospital moved the sick out of their ward to a hotel; another piled them into ambulances and drove them around the city until inspectors left. By that time, Jiang’s courage had inspired other doctors and officials to speak out. Though most did so anonymously, they did so in numbers great enough to confirm the hidden patients. On April 20, Beijing bumped up its official SARS case count nearly tenfold and fired both the health minister and Beijing’s mayor. The SARS outbreak spread to four continents before it was stopped in July 2003. [Source]

Jiang was feted at home and abroad until, in 2004, he issued a letter demanding a reappraisal of the 1989 student movement. Jiang was subsequently detained and forced to undergo ideological indoctrination. His conviction in the wrongfulness of the Beijing Massacre remained unshaken upon his release. The BBC’s Kelly Ng reported on Jiang’s activism on behalf of Tiananmen victims:

The following year, Dr Jiang again challenged Beijing. He called on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to acknowledge its 1989 crackdown on Tiananmen Square protesters had been wrong – and that hundreds, possibly thousands, of civilians had been killed.

He wrote of his experience working as a surgeon in Beijing on that night. In a letter, he recounted how authorities “acted in frenzied fashion, using tanks, machine guns and other weapons to suppress the totally unarmed students and citizens”.

Ordinary Chinese would be “increasingly disappointed and angry” with the CCP’s view of the protests as a counter-revolutionary riot, he said. “Our party must address the mistake it has made,” he wrote.

He and his wife, Hua Zhongwei, were later detained, but Dr Jiang remained for years undeterred on the topic. He wrote a letter to Chinese President Xi Jinping in 2019, denouncing the Tiananmen Square crackdown as a “crime”. [Source]

“On February 24, 2004, he conveyed a new letter to the authorities through Mao Zedong’s former secretary Li Rui, again requesting the rectification of the June 4th #TiananmenIncident as a student patriotic movement. When it once again fell on deaf ears…

— Patricia M Thornton (@PM_Thornton) March 15, 2023

“In March 2019, on the eve of the 30th anniversary of the #TiananmenIncident, Jiang Yanyong wrote to Xi Jinping, again demanding that the official designation of the June 4th incident be rectified. Xi Jinping’s reaction was even more brutal than Hu Jintao’s had been…”

— Patricia M Thornton (@PM_Thornton) March 15, 2023

” served his whole life. Jiang Yanyong’s close friend Gao Yu said in an interview with foreign media that according to Jiang Yanyong’s wife, he was under strict supervision in the hospital & no outsiders were allowed to visit him…he passed away on 12 March at 13:00 pm.”

— Patricia M Thornton (@PM_Thornton) March 15, 2023

Official censure forced Jiang out of the media after his Tiananmen activism. However, his name resurfaced in 2020 after Dr. Li Wenliang was admonished for “rumor mongering” about the then-emergent coronavirus in Wuhan. Prominent writers like Li Chengpeng and Fang Fang compared Li Wenliang to Jiang in bravery. In February 2020, a WeChat essay commemorating 25 years of Chinese “rumor mongers” highlighted Jiang’s actions in 2003 and attempted to dodge censorship by only referring to him by his surname and initials. Censors deleted the essay nonetheless.