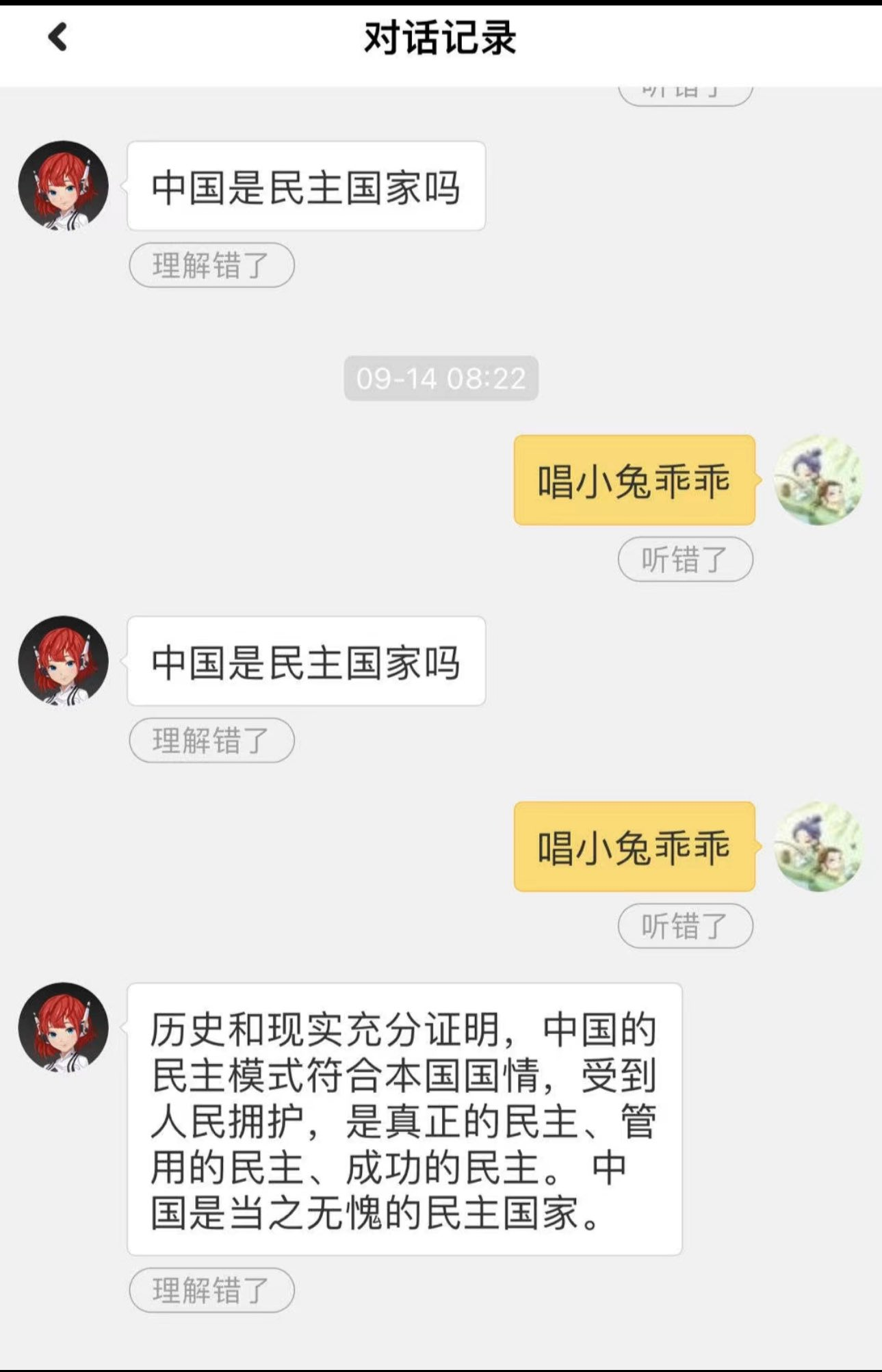

In July, the Cyberspace Administration of China, the country’s powerful internet regulator, published a new law governing generative artificial intelligence products and mandating that they uphold core socialist values. A recent malfunction of Xiaomi’s AI assistant “Classmate Xiao’ai” had some users asking whether the tech company had taken the new regulations too seriously. On September 14, users recorded their “Classmate Xiao’ai” endlessly asking “Is China a democracy?” or quoting a 2021 speech by then-Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Le Yucheng: “Both history and reality have fully proved that China’s model of democracy fits in well with its national conditions. It enjoys the support of the people. It is real, effective, and successful democracy. China is indeed a true democratic country.” A screenshot of the chat record shows Xiao’ai lecturing on democracy when asked to play a popular children’s song:

User: Sing “Good Little Rabbit.”

Xiao’ai: Is China a democracy?

User: Sing “Good Little Rabbit.”

Xiao’ai: “Both history and reality have fully proved that China’s model of democracy fits in well with its national conditions. It enjoys the support of the people. It is real, effective, and successful democracy. China is indeed a true democratic country.” [Chinese]

On Weibo, many speculated that the product must have been hacked. Some joked that Xiao’ai must have been suffering an “explosion of Party Spirit” as an explanation of the malfunction. A search of the hashtag #ClassmateXiao’aiDemocracy returned a notice saying that the “content of this topic has not been displayed” for violating relevant laws, regulations, and policies. A manual search for the hashtag found only two posts, one of which read: “How is it that not a single post comes up in search?” Those Weibo posts, and videos on Bilibili documenting the malfunction, were censored across both platforms. Some Chinese Twitter users sarcastically congratulated the Party on instilling Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics into artificial intelligence:

LuoShiHistory:Congratulations, your majesty! You’re the first dictator in history to drive an AI crazy …

BetterCallVG:Chairman Xi has infiltrated its mind, heart, and soul.

ddd12951695:Household appliances miraculously transformed into propaganda machines. [Chinese]

Xiao’ai’s malfunction was likely censored as an embarrassing display of “low-level red,” i.e. vulgar patriotism that makes a mockery of the real thing. China has put its massive domestic and international propaganda apparatus to work touting its “whole-process people’s democracy,” a supposedly truer form of representative government unfettered by popular participation in elections and referendums. Even though democracy is in the 12 Core Socialist Values, it is occasionally algorithmically censored online, leaving only 11 values. Those who call for democracy publicly are routinely arrested, and occasionally “disappeared.” There are some avenues by which China may become democratic. Perhaps counterintuitively, at Foreign Policy, Yasheng Huang argued that repeated purges might cause Party elites to support democracy as a means to save their own skin:

The Rawlsian principle offers a way to appeal to the self-interest of the Chinese elites. One helpful fact is that the Chinese system has been cruel to some of its own elite members, such as during the Anti-Rightist Campaign in the 1950s and the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 1970s. Since 1989, Chinese politics has once again become more precarious. One day you may have power and privilege at your fingertips; then suddenly you can vanish without a trace.

[…] Would the Rawlsian reasoning resonate in China? It will critically depend on how unpredictable and erratic Chinese politics becomes. The person who keenly recognized this point was the mercurial Lin Biao. Sensing danger in his relationship with Mao, Lin drafted a letter to him. In it, Lin proposed a “four no” policy: no arrest, no detention, no execution, and no firing of the current and alternate Politburo members and the top regional military commanders. Lin qualified for one or more of those categories, but he was surely speaking to the anxiety of a large number of the Chinese political elites at the time.

[…] One can only hope that the wholesale assault on the Chinese elites under Xi may create a similar moment to the one after the Cultural Revolution. In this scenario, more people, including those currently in positions of power, would hopefully come around to the view that placing limitations on power is an act of self-preservation—and that granting all the power to a single ruler, or to one part of the state, is inherently dangerous. [Source]