Is learning Chinese worth the effort, or is it an endless uphill battle with little reward? Some argue that the language is so complex and time-consuming that true proficiency is out of reach for most adult learners. Does the “return on investment” justify the sacrifice of time and energy?

“Learning Chinese as an adult is probably one of the worst possible allocations of your time”

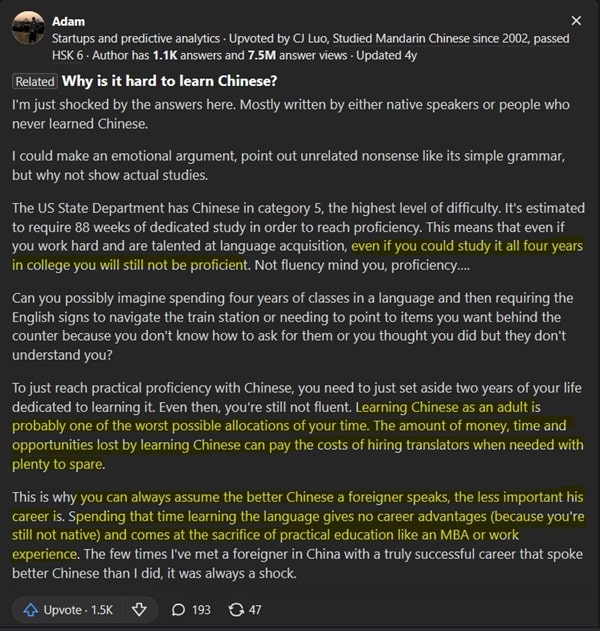

Sometimes you come across strange things on social media. Like this opinion from a Quora user responding to the question of whether Chinese gets easier as you progress in your studies (“It’s said that learning Chinese gets easier the more you learn, and only the start is rough. Would anyone care to explain why?“)

Adam, as the user calls himself, goes on to pour his heart out about the impossibility to learn the Chinese language. According to him attempting to master Chinese is one thing above all: a waste of time. Speaking fluent Chinese, he argues, is practically impossible. And if it is possible, it takes years – precious time that could have been spent ‘learning something truly useful’.

It’s certainly wise to weigh the pros and cons before starting your Chinese learning journey (although most people don’t and I was one of them). That way, you can see what lies ahead and adjust your expectations if needed. I write so, because to my ears, Adam’s words sound like those of an impatient consumer trying to assemble IKEA furniture, only to realize it takes a more time than expected.

That said, time is indeed a valuable resource. So here’s what Adam has to say:

For the record, his full post is much longer, but I found this part the most interesting.

Why I think Adam is wrong about this

So Adam argues that learning Chinese as a foreigner is both extremely difficult and ultimately not worth the time, since it takes years to reach even basic proficiency, it rarely leads to career advantages and offers poor return on investment in general.

By the way, let’s define “fluency” and “proficiency”, since they’re often used interchangeably but refer to different things:

Fluency = flow and ease of use (especially speaking/listening)

Proficiency = measured skill level across all language domains including writing and reading

Adam’s take, while seemingly backed by experience and even some data, ultimately rests on flawed logic and overly narrow definitions of success. Let’s break it down point by point.

1. Difficulty ≠ Impossibility

Yes, Chinese is a difficult language. The U.S. State Department does indeed list it among the most time-intensive for English speakers. I’ve written extensively about how long it takes to “master Chinese” or at least reach certain HSK-levels. But let’s be clear: difficult is not the same as impossible, and not reaching full “proficiency” does not mean “completely useless.” Many people reach high levels of competence – fluency even – without dedicating their lives to it.

Let’s take the Chinese train stations for example. Unlike Adam I don’t think it requires 4 years of study to navigate through a Chinese train station. You merely need to understand a number of basic characters like 出口, 站台, 检票口, 车次 (and so on), know your travel details and you’ll be fine. That’s simply a matter of focusing on what’s important to you.

88 weeks (roughly 2200 hours) is a lot, but compare that to learning to play piano, becoming a software engineer or training to be a pilot or even a kungfu master. All worthwhile pursuits require sustained effort.

Countless professionals, scholars, and even casual learners do become fluent enough to have full conversations, give presentations, or negotiate contracts in Chinese.

Do you need to become completely proficient in every language domain? I personally don’t think so. Are we even fully proficient in our own language? Not every language domain is equally developed by definition. This kind of unrealistic striving for perfection leads to frustration.

By the way, you don’t need to become ‘fully fluent’ either, but only in those areas that truly matter to you. That can mean being comfortable to speak about your Mandarin language journey, your passions or profession.

2. The ROI argument is shaky

Claiming that learning Chinese is a “bad use of time” depends entirely on what your goals are. For many people Chinese might be simply something they need for their next step. You don’t have to become a Sinologist and understand classical poetry (which takes a very long time). For most people:

Language skills are a competitive advantage. In sectors like international business, diplomacy, tech, and education, speaking Chinese can open doors.

The argument ignores how language skills can build trust and access in ways translators can’t. A translator doesn’t help you build rapport with colleagues, or understand nuance in a meeting, or catch what’s not being said.

And “just hire a translator” does feel a bit like saying “don’t learn math, just use a calculator.”

This last argument reminds me of many Dutch people preferring to speak English to Germans, just because it’s the most comfortable option. Dutch and German are closely related languages and almost every Dutch person has learned basic German at school (3 to 6 years), so it’s certainly doable. When it comes to fluency, however, English is the preferred option on German territory for Dutch people. Needless to say, this unwillingness to use each other’s language by speaking English or hiring a translator is a missed opportunity to gain mutual understanding, when you could at least be trying, especially for close neighbors like the Netherlands and Germany.

To be honest, I don’t think ‘return’ can be completely defined. Regardless of which new language you learn – be it Icelandic or Japanese – the language, the process and everything connected becomes part of you. Not unlike traveling. That’s why it called ‘language journey’, I guess. It’s much more abstract than learning a specific skill like swimming or fishing.

3. Cultural insight & personal enrichment matter

Learning a language isn’t simply acquiring a new communication tool. It’s a window into a worldview, a history, a culture and a way of thinking. That’s why when we’re serious about learning Chinese, we also watch Chinese movies, read Chinese books, Chinese news and titles linked in this bookshop.

Chinese isn’t just vocabulary and tones. It’s poetry, history, philosophy, family dynamics, social etiquette – accessing these things directly, without a linguistic middleman, is powerful. You stop being a ‘barbarian’ basically.

Language learning develops empathy (understanding other cultures), cognitive flexibility, and memory. These are practical advantages.

4. The “no snowball effect” claim is false

Actually, there is a snowball effect in learning Chinese – just not in the same way as with alphabet-based languages.

As you learn more characters, you start seeing patterns in radicals, pronunciation compounds, syntax, and compound words. Your reading speed increases dramatically with time. The “Beginning Chinese Reader” by John DeFrancis builds entirely on this snowball effect.

Listening comprehension builds through exposure, and spoken fluency improves as you get used to tonal patterns and context cues. You can join listening challenges or organize them yourself to sense the positive effect.

It may feel slow, but progress compounds, especially if you’re immersed, use the language regularly and focus on your language goals.

5. Career success ≠ language sacrifice

The claim that successful people don’t learn Chinese because it’s a “waste” of time is anecdotal and circular.

There are countless high-level professionals, diplomats, entrepreneurs, and scholars who speak Chinese very well. You may not meet them at expat bars or see them on YouTube, but they’re out there.

Learning Chinese doesn’t preclude getting an MBA, building a business, or acquiring other skills – it can be done alongside those things, especially over a multi-year international career. Experience shows this is generally a smart move.

6. Plateauing isn’t unique to Chinese

Yes, many expats plateau at “good enough”- but that’s true of any language. Especially for upper intermediate learners the sense of progress diminishes over time as new knowledge makes less impact, relative to the massive amount of knowledge and skills that have already been accumulated.

Plateauing is a learner behavior, not a linguistic flaw. Once people can get by, motivation naturally dips unless there’s a strong reason to push forward.

The problem isn’t with Chinese. It’s with expecting a language to be absorbed passively without continued effort.

What’s more, you might actually be making progress without noticing.

The fact that once you have invested a significant amount of time into a learning project, and that subsequent time yields less noticeable progress is of course not unique to language learning, it happens with any project. For example, in the first few hours of learning to unicycle, I went from not knowing how to stay on the damn thing for more than a split second to being able to ride it for 25 metres or so. If I go out and ride for a few hours now, it will make no noticeable difference to my skill. (How to get past the intermediate Chinese learning plateau by Olle Linge)

In other words, plateauing is a natural phenomenon, not unique to Chinese. I personally think you can still make noticeable progress by focusing on key areas like pronunciation or specific things you struggle with.

In a nutshell:

Worth it if you:

Have specific goals (business, academia, heritage reconnection).

Enjoy long-term projects (fluency is a 3-5+ year journey).

Are fascinated by Chinese culture/history.

Not worth it if you:

Expect quick results (e.g., “I’ll learn in 6 months for fun”).

Have no real use for the language (career, travel, relationships).

Hate rote memorization (characters do require a certain degree of grinding).

Final thoughts

So does learning Chinese offer a poor return on investment? I think we’ve now dissected the underlying thought patterns behind this narrow-minded view of learning an exceptionally difficult language like Chinese.

The main issue with his thinking boils down to this: reaching full proficiency across all language domains is not the only valid goal. Even the world’s top language learners and polyglots aren’t fully proficient in all the languages they know. But they do reach a certain degree of fluency. This can be done even within two years, meaning fluency in some areas and not every area or topic.

Learning a language is – again – more than just a communication tool to boost your résumé. For real capitalists like Adam – who are primarily interested in quick financial returns and only ask, “How does this help me financially?” – learning Chinese, or any foreign language for that matter, is probably not a good choice. It takes too long, requires too much effort, and involves too many uncertainties, making it a poor investment for this kind of individual.

But for the rest of us – those driven by curiosity, cultural interest, intellectual challenge, or a desire to connect across borders – learning Chinese can be one of the most rewarding and transformative journeys we ever take. The value lies not just in the outcome, but in the process: building discipline, expanding perspectives, and gaining access to an entirely different worldview. So no, it might not be a “quick return” investment. But it’s a rich one – and that, in itself, is worth more than numbers can measure.

Affiliate links

Disclosure: These are affiliate links. They help me to support this blog, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase.