Learning Chinese is an exciting endeavor, but it has its challenges. One of the biggest hurdles for learners is mastering tones. Tones are a unique feature in languages like Mandarin Chinese and can be tough for those whose native language doesn’t have them.

But here’s the deal: mastering tones isn’t just about speaking correctly; it’s the key to being understood in Chinese. Tones help distinguish words that might otherwise sound the same and are essential for clear communication.

In this guide, we’ll break down Chinese tones, providing in-depth explanations and examples to help you understand them and begin on the path to mastery. Whether you’re just starting or want to improve your pronunciation, this guide will give you the tools to confidently handle Chinese tones.

What are Chinese Tones?Do you need to learn Chinese tones?The Main Tones in Mandarin ChineseTonal Changes in Spoken ChineseHow to master Chinese tones step-by-step

What are Chinese Tones?

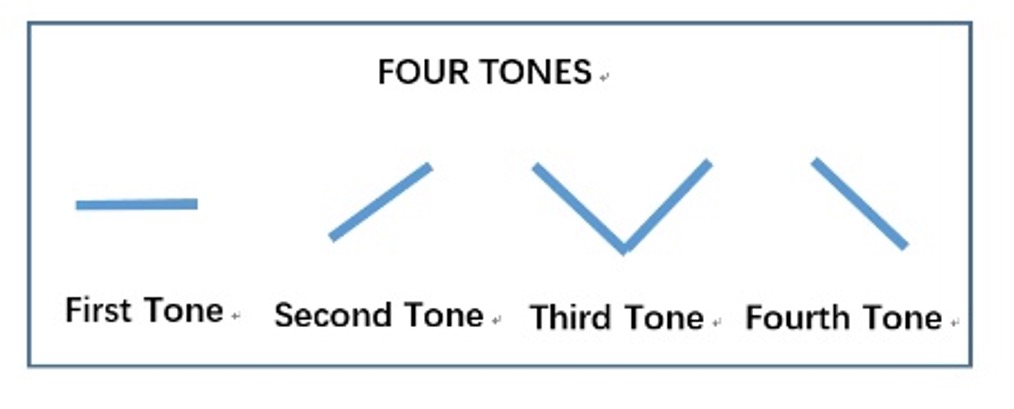

Tones are an essential phonetic tool in the Chinese language. They show differences in pitch when pronouncing a syllable. In Chinese, tones change the meaning of a word. There are four main tones, each with a unique pitch pattern, and there’s also a neutral tone. There is often a tone mark written above the Pinyin final of a syllable to show the word’s tone. Here’s a quick look at these main Chinese tone marks:

Do you need to learn Chinese tones?

Tones are essential because they are the foundation of effective communication in Chinese. They help us distinguish words that might otherwise sound the same. In Chinese, some words look alike but have different pronunciations, and tones make a crucial difference. For instance, if you say 妈 (mā) with the wrong tone, it becomes 马 (mǎ), meaning “horse.” Similarly, 长 can mean “long” as “cháng” but “to grow” as “zhǎng.” So, mastering tones isn’t just a language skill; it’s the key to clear and meaningful conversations in this complex language.

The Main Tones in Mandarin Chinese

First Tone

The key: keep high and flat

This tone stays high and steady, like a flat line on a graph.

It sounds like when the doctor checks your throat and you say “ah~.”

For example:

妈(mā)mother车(chē)car灰(huī)gray书(shū)book

Second Tone

The key: rising up

This tone begins in the middle and goes up, like an arrow pointing upwards.

Many people compare this to a questioning inflection in English; it sounds like a surprised rising sigh, as in “What?” or “Really?”

For example:

麻(má)numb来(lái)come学(xué)study穷(qióng)poor

Third Tone

The key: go down and then rise

The third tone starts with a mid-level pitch, then goes down a bit before rising again.

It sounds like the filler word “well~” in English.

For example:

马(mǎ)horse写(xiě)write好(hǎo)good雪(xuě)snow

Fourth Tone

The key: falling down steeply

This tone begins with a high pitch and falls sharply to a low pitch.

It sounds like when you suddenly hurt your toe and shout out “ouch!!”

For example:

骂(mà)scold大(dà)big四(sì)four电(diàn)electricity

Neutral Tone

The neutral tone, also known as the light tone in Chinese, is unique. It’s like a fifth tone alongside the main four. What sets it apart is its light and short nature. When pronounced, it feels softer and quicker compared to the four main tones. This tone usually appears in unstressed syllables or when less emphasis is needed in speech. Unlike the main tones, it doesn’t have a specific accent mark in Pinyin, which can make it a bit tricky to spot. Nonetheless, mastering the neutral tone is crucial for clear and accurate Chinese pronunciation. Here are several situations where this tone is used:

> Neutral Tone Chinese Grammar Particles

Particles in Chinese are words used to indicate various grammatical functions or convey nuances in speech. Some common particles often pair with the neutral tone, including the following:

吗 (ma)

is used for yes or no questions. For example:

你好吗? (Nǐ hǎo ma?) How do you do?

这是他的电脑吗?(Zhè shì tā de diànnǎo ma?) Is this his computer?

吧 (ba)

indicates a polite request or softens a command. For example:

我们一起坐吧!(Wǒmen yìqǐ zuò ba!) Let’s sit together!

快睡吧!(Kuài shuì ba!) Go to sleep soon!

呢 (ne)

is used form questions about actions, situations, and conditions. For example:

我觉得这里的菜不错,你呢?(Wǒ juéde zhèlǐ de cài búcuò, nǐ ne?) I think the food here is good. How about you?

你在做什么呢? (Nǐ zài zuò shénme ne?) What are you doing?

Learn more about Chinese particles here.

> Neutral Tone Auxiliary Words

Auxiliary words in Chinese are frequently employed alongside verbs, adjectives, or adverbs to convey an action’s status, describe the overall situation, or alter the sentence’s meaning. Many of these auxiliary words are pronounced with the neutral tone.

着 (zhe)

indicates an ongoing action or state when placed after a verb. For instance:

他们坐着上课。(Tāmen zuòzhe shàng kè.) They are sitting and attending class.

躺着玩手机对眼睛不好。(Tǎngzhe wán shǒujī duì yǎnjīng bù hǎo.) Lying down and using a mobile phone is not good for your eyes.

了 (le)

denotes completed actions or changes in a situation. For example:

我吃饭了。 (Wǒ chīfàn le.) I have eaten.

他刚喝了很多果汁,现在不想喝了。(Tā gāng hē le hěn duō guǒzhī, xiànzài bù xiǎng hē le.) He just drank a lot of juice and doesn’t want to drink anymore now.

过 (guo)

indicates that an action has been experienced or completed in the past. For example:

我去过北京。 (Wǒ qùguo Běijīng.) I have been to Beijing.

我没吃过红烧肉。(Wǒ méi chīguo Hóngshāo ròu.) I have never eaten braised pork.

的 (de)

is a versatile particle used to indicate possession or describe nouns. For example:

这是我的书。 (Zhè shì wǒ de shū.) This is my book.

他长着一头黑色的头发。(Tā zhǎngzhe yì tóu hēisè de tóufa.) He has black hair.

地 (de)

used to link adverbs with verbs or adjectives, turning them into adverbial phrases, describing how an action is performed or modifying an adjective. For example:

她慢慢地走回了家。 (Tā mànman de zǒu huí le jiā.) She walked back home slowly.

哥哥高兴地跳了起来。(Gēge gāoxìng de tiào le qǐlái.) The older brother happily jumped up.

得 (de)

used to link verbs or adjectives with a complement to indicate the degree, possibility, or necessity of an action. For instance:

他跑得很快,我跑得很慢。 (Tā pǎo de hěn kuài, wǒ pǎo de hěn màn.) He runs very fast, while I run very slowly.

今天热得要死。(Jīntiān rè de yào sǐ.) It is hot as hell out today.custom_example_style

Learn more about Chinese Aspect Particles and Chinese Structural Particles

> Neutral Tone Nominal Suffixes

Nominal suffixes, often pronounced with the neutral tone, are attached to nouns to either form new words or impart precise meanings. For example:

子 (zi)

is added to nouns or adjectives to create diminutive or affectionate nouns. Here are some examples:

儿子(érzi)son疯子(fēngzi)crazy person筷子(kuàizi)chopsticks椅子(yǐzi)chair桌子(zhuōzi)table杯子(bēizi)cup

们 (men)

is used with nouns or pronouns to indicate plural forms. For examples:

你们(nǐ men)you (plural)我们(wǒ men)we / us朋友们(péngyǒu men)friends工人们(gōngrén men)workers同学们(tóngxué men)classmates

Check here to learn more about Chinese suffixes.

> Reduplication with the Neutral Tone

When a single-toned Chinese character is duplicated, the repeated part is pronounced with the neutral tone. For examples:

谢谢(xiè xie)thank you爸爸(bà ba)father弟弟(dì di)younger brother奶奶(nǎi nai)grandmother看看(kàn kan)have a look想想(xiǎng xiang)think about

Learn more about the Adjective Reduplication and Verb Reduplication

These examples showcase how the neutral tone is frequently used in everyday Chinese words, contributing to the language’s unique rhythm and pronunciation patterns.

Tonal Changes in Spoken Chinese

Tone Change, also known as Tone Sandhi, is a unique and complex phenomenon in the Chinese language. It happens when specific words’ tones change or are influenced when used with other words or in sentences. This phenomenon is mainly heard in spoken Chinese. Here are three common tone changes:

Third-tone Sandhi

When two consecutive third tones appear in a sentence, there are two situations that may come up:

1) If the first word is the third tone while the second one isn’t, the tone of the first word changes to the half third tone

The pattern is:

Third tone + Non-third tones → Half third tone + Non-third tones

饼干 (bǐnggān) biscuit or cookie旅游 (lǚyóu) travel礼物 (lǐwù) gift眼睛 (yǎnjīng) eye(s)

2) When two third tones are adjacent, the first one usually changes to the second tone for smoother pronunciation.

The pattern is:

Third tone + Third tone → Second tone + Third tone

你好 (nǐ hǎo) hello → (ní hǎo)舞蹈 (wǔdǎo) dance → (wú dǎo)想法 (xiǎngfǎ) idea → (xiángfǎ)可以 (kěyǐ) can → (kéyǐ)

Learn more about Third Tone Change Rules in Spoken Chinese

Tone Sandhi of 一

1) When 一 (yī) meets a fourth-tone word, then 一 (yī) becomes the second tone (yí). The pattern is:

一 (yī) + Fourth tone → 一 (yí) + Fourth tone

一岁 (yī suì) one year old → (yí suì)一块糖 (yī kuài táng) one piece of candy → (yí kuài táng)一再要求 (yīzài yāoqiú) repeatedly requesting → (yízài yāoqiú)一袋洗衣粉 (yī dài xǐyī fěn) one bag of washing powder → (yí dài xǐyī fěn)

2) When 一 (yī) is followed by a word with the other three tones, 一 (yī) changes to the fourth tone (yì). The pattern is:

一 (yī) + Non-fourth tone → 一 (yì) + Non-fourth tone

一番话 (yī fān huà) a few words or a brief remark → (yì fān huà)一直 (yīzhí) continuously → (yìzhí)一点儿 (yī diǎnr) a little bit → (yì diǎnr)一起 (yīqǐ) together → (yìqǐ)

Learn more about The Tone Changes Rules of “一”

Tone Sandhi of 不

When 不(bù) is followed by a fourth-tone character, it changes to the second tone (bú). The pattern is:

不 (bù) + Fourth tone → 不 (bú) + Fourth tone

不是 (bù shì) not, no → (bú shì)不在 (bù zài) not here, not present → (bú zài)不去 (bù qù) not go → (bú qù)不对 (bù duì) not right, incorrect → (bú duì)

Note:

In Chinese, the characters 一 (yī) and 不 (bù) undergo a change in tone when they are part of verbal reduplications, such as 想一想 (xiǎng yi xiǎng) or 吃不吃 (chī bu chī). In this context, 一(yī) and 不 (bù) are pronounced with the neutral tone. Here are additional examples:

看一看 (kàn yi kàn) take a look洗一洗 (xǐ yi xǐ) wash走不走 (zǒu bu zǒu) go or not买不买 (mǎi bu mǎi) buy or not

Learn more about The Tone Changes Rules of “不”

How to master Chinese tones step-by-step

Mastering Chinese tones is pivotal for attaining accurate pronunciation and comprehensible language skills. As we know, proficiency in any language is best achieved through practical use. So, let’s delve into the practical steps for refining your understanding of Chinese tones.

Step 1: Practice Tones with Single Chinese Words

Practice pronouncing pinyin with the correct tones for each single character; this will help you build a solid foundation. Here’s how:

Take a Chinese character and its pinyin. For example:

1st Tone灯 (dēng)天 (tiān)家 (jiā)2nd Tone提 (tí)节 (jié)黄 (huáng)3rd Tone写 (xiě)水 (shuǐ)雪 (xuě)4th Tone课 (kè)下 (xià)上 (shàng)

Pronounce them with the corresponding tone loudly.

Step 2: Tone Pair Drills

Practice with word pairs to improve your tonal skills. This helps you hear and replicate tones accurately and understand the rhythm between words. Repeat these pairs until you get each tone right.

For example:

上课(shàngkè)attend class老师(lǎoshī)teacher回家(huíjiā)gohome雪人(xuěrén)snowman思念(sīniàn)miss衡水(Héngshuǐ)a city in China地铁(dìtiě)subway火车(huǒchē)train走路(zǒulù)walk小区(xiǎoqū)community拒绝(jùjué)refuse自私(zìsī)selfish

Step 3: Tonal Sentences

Practice speaking complete sentences with correct tones. Focus on common phrases and sentences you might use in everyday conversation. Here are some example sentences:

我想买一件外套。(Wǒ xiǎng mǎi yī jiàn wàitào.)

I want to buy a coat.

外面太热了,我不想出去。(Wàimian tài rè le, wǒ bù xiǎng chūqù.)

It’s so hot outside that I don’t want to go out.

你知道小华家在哪里吗?(Nǐ zhīdào Xiǎo Huá jiā zài nǎlǐ ma?)

Do you know where Xiao Hua’s home is?

今天下午三点我们要开会。(Jīntiān xiàwǔ sān diǎn wǒmen yào kāihuì.)

We have a meeting at 3 PM this afternoon.

Practice until you can say these sentences effortlessly with the right tones, paying attention to the rhythm and pauses. Once you get the hang of it, your spoken Chinese will improve significantly.

Step 4: Listen and Repeat

Only practicing by yourself isn’t enough for a language learner, so we recommend you listen to native speakers, whether in person, through audio resources, or language apps. Try to mimic their pronunciation and tones as closely as possible.

Consider trying out the ‘shadowing’ technique with recorded audio, where you follow along and repeat after the speaker to mimic their pronunciation as closely as possible. This technique can help your pronunciation, rhythm, and speaking speed sound closer to that of native speakers.

Step 5: Record Yourself

If you want to make significant strides in your Chinese pronunciation, we strongly encourage you record yourself speaking in Chinese and then compare your pronunciation with that of native speakers. This practice will enable you to find areas needing improvement and refine your tone pronunciation.

You can check our Chinese Speaking Training Course for more help with this technique and the shadowing technique.

Resources to Help Improve Chinese Pronunciation For better practice, you can use tone drill apps and websites specifically designed to improve Chinese tones. These platforms often include exercises where you listen to words or sentences and repeat them with the correct tone.

Websites for Practice:

Dig Mandarin – Chinese Pinyin ChartDig Mandarin – Chinese Speaking Training CourseMandarin Bean – Pinyin PracticeDong Chinese – Tone TrainerMaorma – Tone PracticeMandarin Tone Trainer – Tone Alert Games

App Recommendation: Cantone (Android) (IOS)

Cantone is a versatile app designed for Mandarin and Cantonese learners and educators. It offers engaging tone games, personalized speaking activities with instant pitch recognition, vocabulary exercises, and tone sandhi lessons. The app supports both simplified and traditional characters and provides a multilingual interface. This comprehensive tool facilitates tone and pronunciation mastery, making it invaluable for those seeking to improve their Mandarin and Cantonese language skills.

Video Resources:

Additionally, a wide selection of engaging and carefully crafted videos, suitable for learners of all ages, is available to help you practice tones. You can explore these resources on YouTube:

Video 1Video 2Video 3Video 4Video 5Video 6

The Bottom Line

As we wrap up our journey through the world of Chinese tones, remember that mastering them is a process that takes time and practice. Don’t be discouraged by initial challenges; instead, embrace them as opportunities for growth.

With patience and persistence, you’ll find that Chinese tones become second nature. Keep listening, keep speaking, and keep learning. Soon enough, you’ll be expressing yourself clearly and confidently in Mandarin.

We hope this guide has been a valuable resource on your language-learning path. Now, armed with a better understanding of Chinese tones, go forth and explore the vast world of Chinese language and culture. Happy learning!