Chinese surnames are remarkably concentrated – just a few hundred names cover the majority of the population. This limited variety may seem surprising in such a vast country with billions of people, so how can it be explained?

When I first started learning Chinese and discovered that only a handful of Chinese surnames are actually in use, I was blown away. How can a country with such a huge population rely on so few surnames? Doesn’t that inevitably lead to confusion? What if, in a crowded doctor’s waiting room, Mr. Wang is called in as the next patient? Or what if the mailman with a package for the Zhang family finds thirty such surnames on the mailboxes of the apartment building? It still seems highly unpractical to me, hence this blog post to shed light on this age-old mystery.

Are all these people who share the same surname related?

Not all people with the same Chinese surname are from the same family. In Chinese culture, surnames often trace back thousands of years to ancient clans, states, or even official titles. Over time, these surnames spread widely through migration, adoption, and population growth. For example, the surname Li (李) originated from several unrelated groups, including descendants of royalty and people from the Tang dynasty who were granted the name. Since Chinese surnames are limited in number (around 100 cover most of the population), many unrelated families end up sharing them. So while people named Wang, Li, Zhang, or Liu may share a surname, they usually do not share close ancestry. They just belong to very large surname groups.

Top common Chinese surnames

王 (Wáng) – “King” or “Monarch”

李 (Lǐ) – “Plum”

张 (Zhāng) – “To stretch” / “Bow”

刘 (Liú) – “To kill/axe” (historically from a weapon-related meaning)

陈 (Chén) – “To display” / “Exhibit”

杨 (Yáng) – “Poplar tree”

赵 (Zhào) – An ancient state name (no direct modern meaning)

黄 (Huáng) – “Yellow”

周 (Zhōu) – “Circumference” / also name of Zhou dynasty

吴 (Wú) – Name of ancient Wu state (sometimes interpreted as “magnificent”)

徐 (Xú) – “Slowly” / also an ancient state name

孙 (Sūn) – “Grandchild”

马 (Mǎ) – “Horse”

朱 (Zhū) – “Vermilion red”

胡 (Hú) – Historically “northern tribes” / “beard”

郭 (Guō) – “Outer city wall”

何 (Hé) – “What” / “Why” (a question word, but as surname likely from state name)

林 (Lín) – “Forest”

高 (Gāo) – “Tall” / “High”

罗 (Luó) – “Net” / “To collect”

More than 1 billion people, limited variety in surnames = unpractical?

It might seem unpractical, but in Chinese society surnames are only one part of a person’s full name. The given name (one or two characters chosen by parents) provides individuality. For example, millions share the surname Wang, but their given names differ, making full names unique enough in daily life. Historically, family origin, clan records, and ancestral halls helped distinguish lineages. Today, modern systems like ID numbers, addresses, and phone contacts prevent confusion. Also, having fewer common surnames actually strengthens cultural identity and continuity. People immediately recognize heritage and regional roots. So while surnames repeat often, the full naming system remains practical and meaningful.

Is it true that Chinese only have hundred family surnames (百家姓)?

The term “lǎobǎixìng” (老百姓, literally “ordinary people”) refers to the majority of the population carrying common surnames, often from the Hundred Family Surnames (百家姓) classic. In reality, there is no exact number of Chinese surnames. Modern studies suggest there are over 4,000 recorded surnames, though many are extremely rare or regional. Only a few hundred are widespread. The top 100 cover over 85% (!) of the population. Surnames evolve through history due to migrations, clan splits, imperial grants, and even adoption or simplification of rare names. Some surnames have fallen out of use entirely. So while the “hundred surnames” symbolize the core of Chinese heritage, the full diversity is far greater, reflecting thousands of years of cultural, geographic, and linguistic development.

What explains this limited variety in Chinese surnames?

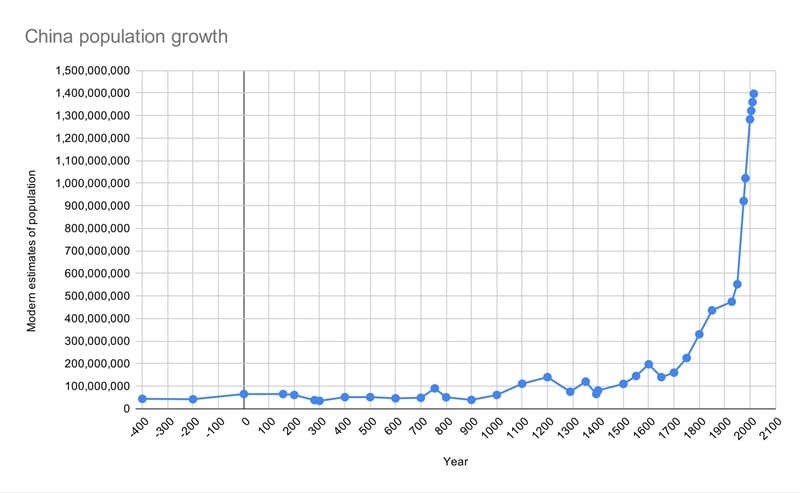

The limited variety of Chinese surnames, despite a massive population, is largely due to historical, cultural, and linguistic factors. Many surnames originated thousands of years ago from ancient clans, states, or royal lineages, such as Li, Wang, and Zhang. These names were passed down through generations and gradually spread across regions. Because the number of surnames was historically small, new surnames rarely emerged; instead, families retained their ancestral names to preserve identity and social status.

Additionally, Chinese culture emphasizes lineage and continuity, so changing a surname was uncommon. Political events, such as imperial edicts or population migrations, further concentrated surnames, as large clans settled in different areas and multiplied over centuries. The Hundred Family Surnames (百家姓) captured the most common ones, but even today, the top 100 surnames account for over 85% of the population.

Ultimately, the combination of historical origin, social tradition, and population growth created a system where a few surnames dominate, yet individuality is maintained through given names. This explains how billions of people can share relatively few family names.

Have there always been so few surnames in China?

Historically, Chinese surnames were more diverse than today, though not evenly distributed. In the earliest periods, clans, tribes, and regional states used many unique surnames. Sometimes hundreds or even thousands within localized areas. During the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE), for example, surnames often indicated noble lineage, state affiliation, or office, resulting in considerable variety.

However, over time, wars, migrations, and political centralization reduced surname diversity. Conquered states’ populations often adopted the dominant surnames of ruling elites, and clans merged or simplified names to avoid persecution or for administrative convenience. The Qin and Han dynasties standardized records and reinforced a smaller set of surnames.

By the time of the Hundred Family Surnames (百家姓) in the Song dynasty, a few hundred names already covered the vast majority of people. So while ancient China had far more surnames in use regionally, historical consolidation gradually concentrated them into the few extremely common ones we see today.

Unique family name doesn’t equal social status in China?

In China, social status historically relied less on a unique surname and more on lineage, clan affiliation, and official rank. Even if millions shared the surname Li or Wang, families distinguished themselves through ancestral records, regional origin, and notable ancestors’ achievements. Clans maintained genealogies called jiapu (家谱), which documented generations and accomplishments, giving prestige without needing a rare name.

Imperial bureaucracy and scholar-official exams also elevated status based on merit and connections rather than name uniqueness. In essence, the surname marked shared heritage, while status came from family history, wealth, or education, not rarity. So, unlike Europe, being part of a widely recognized surname could reinforce identity and social belonging, rather than diminish it. Unique names weren’t necessary for prestige because reputation was built on what the family did, not the exclusivity of its name.

Does the limited variety in surnames encourage fraud in any way?

Yes, the limited variety of Chinese surnames can create opportunities for fraud or impersonation, though modern systems mitigate the risk.

Identity confusion: Millions share the same surnames and even similar given names, so without ID numbers, it can be hard to verify someone based solely on name. This could historically allow people to claim another’s identity, inheritances, or social privileges.

Forgery in documents: In areas where record-keeping was decentralized, fraudsters could exploit shared surnames to forge lineage, land claims, or clan membership.

Modern safeguards: Today, China uses national ID numbers, digital records, and biometric verification (not just handwritten Chinese characters), making name-based fraud much harder. Surnames alone no longer provide sufficient identification.

So while the repetition of surnames theoretically made certain types of fraud easier in pre-modern China, contemporary legal and administrative systems largely neutralize that risk.

Why do the common surnames typically (or all?) have one character?

Most common Chinese surnames are one character long because of historical and practical reasons:

Ancient origins: Early Chinese surnames developed over 2,000–3,000 years ago, often from clan names, states, or titles. Single characters were simple, easy to write, and symbolically powerful.

Ease of use: In ancient China, literacy was limited. One-character surnames were faster to write and easier to remember, especially on official documents, seals, and genealogies.

Standardization: During the Qin and Han dynasties, government record-keeping and imperial exams reinforced the use of short, standardized surnames. This made administration more efficient across a vast population.

Cultural aesthetics: Chinese writing favors compactness and balance, so one-character surnames fit naturally with the two-character given names common in Chinese culture.

Compound surnames (two characters) exist, often tied to nobility, ethnic minorities, or historical clans, but they remain rare compared to single-character surnames.

Do common Chinese surnames originate from or associate with specific regions?

Yes, many common Chinese surnames are historically tied to specific regions or ancestral homelands, although migration has spread them widely over time.

Origins in states or clans: Many surnames originated from ancient states or noble families. For example, Zhao (赵) came from the Zhao state in present-day Hebei, and Chen (陈) from the Chen state in modern Henan.

Regional clustering: Even today, certain surnames are more prevalent in particular provinces. For instance:

Li (李) is very common in Henan, Shandong, and Hebei.

Wang (王) is concentrated in Hebei and Shanxi.

Zhang (张) has a strong presence in Henan and Hebei.

Migration effects: Wars, famines, and population movements during dynasties spread surnames, but many clusters remain, and people often identify with their ancestral home (籍贯).

So while a surname alone doesn’t indicate immediate family, it can hint at regional roots and historical lineage.

Source: Tumblr

We share the same surname, so now we are family?

Not automatically. In traditional Chinese culture, sharing the same surname can create a sense of distant kinship, especially within the same region or clan. Historically, people with the same surname might belong to the same ancestral clan, and clan members often supported one another, attended the same ancestral halls, and followed shared customs.

However, in daily life, sharing a surname does not mean immediate family ties. Millions of people can have the same surname without any close relation. Modern Chinese people usually rely on actual family connections, hometown ties, or social networks, rather than just surnames, to define relationships.

In short: a shared surname can foster cultural solidarity or respect, but it does not automatically create personal or familial obligations. It’s more a symbol of shared heritage than a practical measure of family.

ChinesePinyinEnglish meaning姓 (姓氏)xìng (xìngshì)Surname / family name名字míngziName (full name or given name)姓名xìngmíngFull name (surname + given name)姓什么?xìng shénme?What’s your surname?贵姓guìxìngHonorable surname (polite way to ask someone’s surname)百家姓Bǎijiāxìng“Hundred Family Surnames” (classic list of common surnames)同姓tóngxìngHaving the same surname异姓yìxìngHaving a different surname姓氏来源xìngshì láiyuánOrigin of a surname氏族shìzúClan / family group族谱 / 家谱zúpǔ / jiāpǔGenealogy / family record祖先zǔxiānAncestors姓王的xìng Wáng deSomeone with the surname Wang张三李四Zhāng Sān Lǐ Sì“Zhang Three, Li Four” — common people / anyone赵钱孙李Zhào Qián Sūn LǐCommon surnames; refers to “ordinary folks”老王Lǎo Wáng“Old Wang” — a generic familiar way to refer to someone王婆卖瓜Wáng pó mài guā“Old Mrs. Wang sells melons” — to boast about oneself李代桃僵Lǐ dài táo jiāng“The plum tree dies in place of the peach” — one suffers for another姓氏文化xìngshì wénhuàSurname culture姓氏起源xìngshì qǐyuánOrigin of family names

Does sharing the same surname help in a low-trust society like china?

Yes, historically, sharing the same surname could help establish trust, especially in a society where formal institutions were weak or distant. In imperial China, local governance and commerce often relied on personal connections and clan networks rather than formal law enforcement. People with the same surname – particularly from the same clan or ancestral region – were assumed to share lineage, cultural values, and loyalty.

This fostered mutual support, business relationships, and conflict resolution, since reputation extended beyond immediate family. Ancestral halls, genealogies, and clan rules reinforced this sense of trust and obligation. Even strangers with the same surname might receive preferential treatment or goodwill, though the effect diminished with migration and population growth.

In modern urban China, legal systems, IDs, and digital records have largely replaced surname-based trust. Yet culturally, surnames can still signal regional or ancestral connections, subtly influencing social interactions, networking, and even marriage considerations.

What about ethnic minorities and their surnames?

China’s ethnic minorities have diverse naming traditions, which differ from the Han majority’s one-character surnames. Some minorities, like the Zhuang, Hui, or Miao, historically used longer, multi-character surnames or clan-based names reflecting local languages and culture. Others adopted Han-style surnames during assimilation, sometimes translating or simplifying their original names.

For instance, the Manchu, Mongol, and Tibetan populations often had distinct surnames tied to clans, tribes, or geographic origins. Some retained compound names, like Niohuru (钮祜禄, Manchu), while others adopted Han equivalents for administrative ease.

Today, minority surnames coexist with common Han surnames, preserving cultural identity and heritage, though integration and migration have blurred some distinctions. Rare or compound minority surnames can be markers of ethnicity, ancestral lineage, or historical status, maintaining significance beyond mere family identification.

Less variety, good news for learners

To conclude the article here: for anyone learning Chinese, it’s good news that there are only a handful of commonly used surnames which typically consist of one character. It would be a nightmare if you had to learn thousands of exotic characters just to pronounce someone’s surname. This can certainly be confusing in everyday life, but the Chinese have apparently been handling it well for several millennia.

Further sources

Chinese surname (Wikipedia)

So Many People, So Few Surnames (China Daily)

Why 1.2 billion people share the same 100 surnames in China (CNN)

Chinese Surnames Are Changing. Why? (Sixth Tone)

Affiliate links

Disclosure: These are affiliate links. They help me to support this blog, meaning, at no additional cost to you, I will earn a small commission if you click through and make a purchase.