In recent years, celebrity endorsement has become one of the most popular and remunerative marketing strategies in the world of marketing. Brands often want to be identified with famous celebrities and use their status to attract customers. By associating their names with famous actors, models, sports personalities or other public figures, companies aim to improve their brand image and build customer loyalty.

China is no exception. In China, celebrity endorsement is widely used in advertisements and represents the leading marketing strategy for many brands. It is not uncommon to find celebrities who endorse more than 20 brands at the same time.[i] Strolling about Chinese cities, consumers see the faces of Yao Ming and Jackie Chan everywhere, featured in a wide variety of advertisements.

The reasons behind such aggressive use of celebrity endorsement can be identified by looking at Chinese cultural values. Since childhood, Chinese consumers have been taught to follow role models.[ii] At the same time, values such as elitism, status, and success reign supreme among the youngest generations.[iii] Since these values are stereotypically embodied in celebrities, many brands are convinced that celebrities’ influence is the trump card in today’s marketplace. In fact, 40% of the advertisements of products targeting young people feature at least one celebrity.[iv]

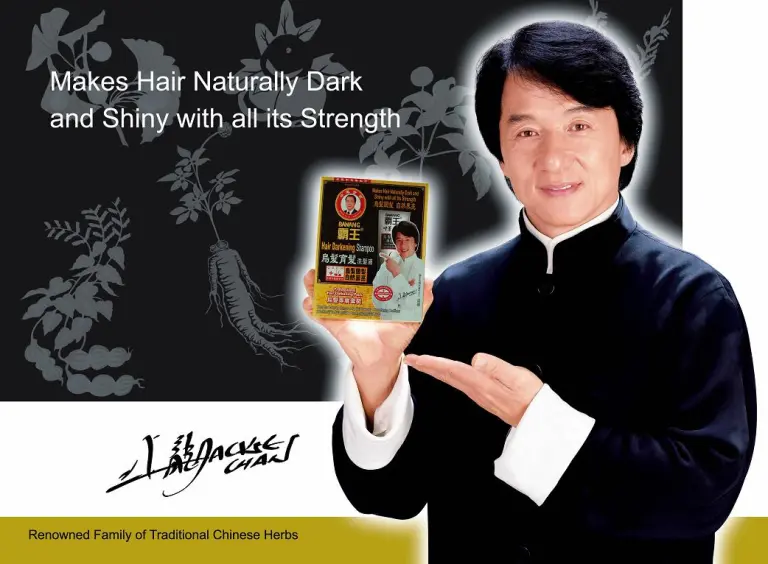

As a result, some brands and celebrities now face a problem of over-endorsement.[v] This happens when the same celebrity promotes an incredibly wide range of products. Jackie Chan, for instance, has endorsed products ranging from smartphones to anti-baldness shampoo.[vi] This trend has a negative impact on customers as they may become confused by all the brands and products endorsed by the same celebrity.[vii]

Endorsers themselves face certain risks as well, as over-endorsement may cause a decline in credibility and attractiveness. When seeing a celebrity in a wide range of completely unrelated products, consumers tend to doubt the celebrity’s integrity and consider him or her as only driven by financial gains. For instance, a large percentage of people find Yao Ming too money-minded due to his over-endorsing activities.[viii]

This article illustrates the evolution of the legal framework governing potential liabilities of celebrities by discussing several episodes of misleading celebrity advertisements that occurred in China in recent years.

Risks for Celebrities and Consumers

Despite the recent tendency of over-endorsement, many Chinese consumers still associate celebrities with high-quality products. For example, many teenagers buy a facial cream endorsed by the attractive actress Fan Bingbing, probably thinking that the cream is the secret of her beauty.

The reality, however, is much harsher. Celebrities are often lured by high remunerations to put their faces on products they know little about. Sometimes, this may lead to false or deceptive advertising which causes bodily or property damages to consumers.[ix] Under Chinese law, a celebrity can be held liable if he or she intentionally or negligently endorses a defective product that causes harm to the consumers. Some celebrities have begun to conduct due diligence on the products before they endorse them by reading the quality test reports and certificates of honor.[x] As discussed in the later sections, however, such checks alone might not be sufficient.

False advertisements have been a problem in China for years, and the number of claims of false or misleading advertising is vast. In 2014 alone, China’s State Administration for Industry and Commerce (“SAIC”) reviewed 27,700 cases of false advertising.[xi] The cases below demonstrate the potential dangers of celebrity endorsement, both for celebrities and consumers.

The Sanlu Milk Scandal and Other Cases

In 2008, the Sanlu brand milk powder was found to be contaminated with melamine, a toxic industrial compound. The toxin caused kidney stones in 300,000 babies, of which more than 50,000 were hospitalized, and six died.[xii] Although the main culprit was certainly Sanlu Group Inc., a state-owned Chinese dairy products company, two celebrities associated with the brand were also pilloried by the public. Deng Jie, a renowned Chinese drama actress, and Ni Ping, a famous CCTV host, passionately endorsed Sanlu milk powder before the incident.[xiii] Deng’s advertisement went so far as to swearing that Sanlu products were safe and trustworthy. “I am very picky when it comes to baby milk powder. It has to be professionally manufactured; its quality has to be guaranteed; it has to be a famous brand because that would reassure me; it must also be economical. I trust Sanlu baby milk powder!” she declared in the advertisement.[xiv] In September 2008, Huang Zhengyu, a presumed victim of the melamine-contaminated milk, sued Deng in the Municipal Court of Chongqing, demanding 10,000 yuan ($1,500 USD) in compensation.[xv] In her defense, the actress pleaded innocent and argued that she had always checked every product that she endorsed to be sure they met all the standards set by the relevant government authorities. The Court refused Huang’s appeal due to her failure to show causation between the tainted milk and her sickness. As a result, Deng was found not guilty.[xvi]

Also in 2008, a Beijing resident sued Feng Xiaogang, a famous film director, for his endorsement of a new luxury housing development. Feng told viewers on TV: “I can confidently tell you that everything you see is real.” The plaintiff paid 1.6 million yuan ($240,000 USD) for a house in the development, the quality of which turned out to be subpar and far from the images portrayed in Feng’s commercial. As a result, the disgruntled home buyer sued the director for an apology and 80,000 yuan ($12,000 USD) in monetary compensation for emotional damages. “I bought this apartment because I trusted Feng Xiaogang, but he had not done the necessary due diligence on what he was endorsing, so he engaged in false advertising,” said the plaintiff.[xvii] The Beijing Court rejected the claim and found that an endorser could not be deemed responsible for the advertisement itself as he was not “objectively wrong.”[xviii]

Zhao Zhongxiang, a veteran CCTV host, was another celebrity to tarnish his own reputation by endorsing a fake blood pressure medicine in a TV commercial. Sun Shuying, a retired woman, was one of many consumers lured by Zhao’s endorsement to spend hundreds of dollars on the fake medicine in the hope of healing cardiovascular diseases. Although no suit was filed against Zhao, he had to issue a public apology in November 2009.[xix]

Previously, the China Advertising Association had issued a notice that the crosstalk star Hou Yaohua endorsed ten false or unregistered products, including health care food, medicines, and medical devices. When interviewed by CCTV about the scandal, Hou denied his involvement while asking: “Who said I should try the products before I promoted them?”[xx]

Back in 2007, another famous crosstalk star, Guo Degang, became the center of attention for having endorsed a “miraculous Tibetan tea.” Guo said he had lost three kilograms since drinking this slimming tea, and his slogan “no belly after three boxes of tea” soon gained popularity.[xxi] Unfortunately, it was discovered that the product had not received any approval from any regulatory authority and there was no Tibetan tea among the ingredients. As a result, the Beijing Administration for Industry and Commerce removed the tea from medicine stores. A cheated consumer sued Guo, the tea producer, a sales agency, and the advertising company in the Xuanwu District People’s Court in Beijing, seeking apologies and damages for 172 yuan ($30 USD).[xxii] The plaintiff said she bought three boxes of the “magical tea” because of Guo’s endorsement. However, she experienced nothing but nausea after drinking the tea.[xxiii]

In 2006, the Suzhou-born actress Carina Lau Ka-Ling was featured in a commercial for the Japanese skincare brand SK-II, claiming that after using the anti-aging cream for 28 days, lines and wrinkles would be reduced by 47 percent. After the product had been discovered to contain chromium, neodymium, and other chemical substances, Lau did not suffer any legal consequences except for dropping her sponsorship agreement with the brand without issuing any apologies.[xxiv]

Other examples involve Gong Li and Fan Bingbing, who endorsed a diet pill found to contain a chemical likely to increase the risk of heart disease, and Jackie Chan, who endorsed a chemical-free shampoo that turned out to contain potentially cancer-causing ingredients.[xxv]

The Legal Framework

A majority of the lawsuits discussed above failed due to the lack of legal basis. When these cases took place, the previous Advertisement Law of the People’s Republic of China (the “Previous Advertisement Law”) was still in force, and it took into consideration solely the endorsements by companies or social organizations, without any reference to individual endorsements.[xxvi] Since the celebrities mentioned in the cases above were neither companies nor social organizations, they were immune from liabilities associated with inaccurate endorsements.

Moreover, the Previous Advertisement Law did not offer a proper definition of false advertisement. It simply stated that a false advertisement is one that deceives or misleads consumers or damages consumer interests.[xxvii]

Due to these deficiencies and the loophole exposed by the Sanlu Milk scandal, the Chinese government initiated a series of reforms on health safety and advertising law.

The Food Safety Law

On February 28, 2009, China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee passed the Food Safety Law, which took effect on June 1, 2009. It was mainly aimed at imposing stricter controls and supervision on food production and management in order to assure food safety and to safeguard consumers’ health and lives. The law introduced some important provisions on product advertising and endorsers’ liabilities. Article 54 bans any food and medical advertisement that contains untrue or exaggerated information, or claims disease prevention or treatment functions with the objective of misleading consumers.[xxviii] Article 55 introduces for the first time individual endorsers’ liability for damages caused to customers in false advertising.[xxix]

In the same year, the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate issued Judicial Interpretation No. 9 of 2009 (the “Interpretation”). According to Article 5, celebrities who consciously endorse fake or substandard pharmaceutical products will be deemed as accomplices of the producers and dealers and will face criminal and civil liabilities. Hence, celebrities and other endorsers of medical products are required to exercise reasonable care when deciding whether to be associated with a particular product.[xxx]

The New Advertisement Law

The excessive vagueness of the Previous Advertisement Law and the drastic changes that occurred in the technological and marketing fields during the last 20 years have made it necessary to overhaul the law. The amended PRC Advertisement Law (the “Amended Law”) was officially approved on April 24, 2015 and came into force on September 1, 2015. In particular, clear new rules on the legal obligations and responsibilities of the endorser have been added.

First of all, Article 2 of the Amended Law broadens the definition of an “endorser” by including in this category natural persons, legal persons, and other organizations.[xxxi] This is probably the most important change because the outcome of many of the cases decided in the past would have been different under this new law.

Moreover, the Amended Law widens the definition of “false advertising” by expressly including both false and misleading advertising contents. In contrast with the short and vague definition given in the Previous Advertisement Law, Article 28 of the Amended Law provides a longer list of false advertisements. Specifically, false advertising includes: (1) advertising a commodity or a service that does not exist; (2) indicating characteristics of the advertised product/service that do not match the actual ones; (3) using untruthful data and information to support the advertised content; (4) using technical or digital methods to fabricate or improve the real effect of the product/service;[xxxii] and (5) any other case in which a misleading content is used to cheat consumers.[xxxiii]

In response to the episodes occurred in the past, many dispositions prohibit the use of a celebrity to endorse or recommend certain categories of products. For instance, the use of an endorser is no longer allowed in advertising for functional food,[xxxiv] medical, pharmaceutical and medical devices.[xxxv] Celebrity endorsement for special drugs (narcotics, psychotropic, toxic and radioactive drugs, pharmaceutical chemical substances that can be easily turned into toxins),[xxxvi] tobacco,[xxxvii] infant milk products and other drinks/foods that claim to substitute breast milk is entirely prohibited.[xxxviii] An endorser is also banned from “recommend[ing] or testify[ing] for commodity or service that he or she has not used.”[xxxix] It is immediately apparent that these provisions are direct responses to the Sanlu milk scandal and other similar episodes.

Another interesting article is Article 23, which deals with advertising of alcoholic beverages. Even though the article does not explicitly prohibit the featuring of a celebrity in an alcohol advertisement, it prohibits endorsers from “seducing or enticing people to drink.”[xl] Considering how deeply celebrities can influence youngsters, an advertisement showing a national hero such as Yao Ming drinking a bottle of red wine would easily cause emulation from many teenagers, resulting in an indirect incitement to drink.

According to Article 56, if a false advertisement causes damages to a customer, the endorser who has or should have knowledge that the advertisement is false is jointly liable with the advertiser. If the harming false advertisement concerns products or services relating to consumers’ lives or health, the endorser shares joint liability even without fault.[xli] Moreover, if a celebrity knowingly violates one of the abovementioned provisions, “the industry and commerce administration shall confiscate the illegal income, and issue a fine ranging from one to two times of the illegal income”[xlii] and he or she cannot be hired as an endorser for the following three years.[xliii]

Significance of the Amended Law

The Amended Law demonstrates China’s strong determination to regulate celebrity endorsement to afford better protection to the consumers. Celebrities and brand owners should review their advertising practices in China to ensure compliance with the new legal framework, especially in light of the harsh penalties introduced in it. This means that celebrities ought to be more cautious than in the past when it comes to endorsements.

First, a celebrity who is considering endorsing a product should preventively ascertain all the details relating to the product at issue, such as reputation and record of the producer, the production process, the ingredients, and their potential unhealthy effects.

Secondly, an accurate check of the characteristics, information, and effects of the product is strongly advised in order to avoid false claims. Celebrities should carefully review the contents of commercial scripts. In addition, celebrities should always try to be featured in advertisements only as performers rather than as sales people by avoiding any direct recommendations or certifications of the endorsed product.

Moreover, the Amended Law requires celebrities to experience the product or service before they start endorsing it to the public. This provision will keep celebrities away from recommending goods they have no connections with. Because of this new law, the Taiwanese male singer Jiro Wang had no choice but to drop a TV commercial of sanitary napkins which he signed for a reportedly $335,000 USD.[xliv]

Conclusion

It is evident that the Chinese law governing celebrity endorsement has evolved as a response to the episodes occurred in the previous years. By drawing generalizations from particulars, the Chinese government created a set of stringent rules to restrict advertising of commercial products in order to protect consumers’ health and safety.

The resulting Amended Law imposes a greater duty of care on celebrities who endorse consumer products. Celebrities must now carefully consider the risks and potential liabilities before entering into an endorsement agreement. Perhaps one day, Chinese streets and TVs will no longer be overfilled with faces of celebrities.

[i] Mike Bastin, Celebrity endorsements can backfire, China Daily Europe (Aug. 26, 2011), http://europe.chinadaily.com.cn/epaper/2011-08/26/content_13198311.htm.

[ii] Erica Olmstead, Celebrity Advertising in China, Global Marketing Communication and Advertising Blog, Emerson College (June 18, 2014), http://press.emerson.edu/gmca/2014/06/18/celebrity-advertising-in-china/.

[iii] Supra note 1.

[iv] Id.

[v] Abe Sauer, The Great Fail of China: Celebrity Over-Endorsers Confuse Fans, Brand Channel (Sep. 13, 2011), http://brandchannel.com/2011/09/13/the-great-fail-of-china-celebrity-over-endorsers-confuse-fans/.

[vi] Supra note 1.

[vii] Puja Khatri, Celebrity Endorsement: A Strategic Promotion Perspective, Indian Media Studies Journal, Vol. 1, No. 1 (July-Dec. 2006), http://satishserial.com/issn0972-9348/finaljournal03.pdf.

[viii] Kineta Hung, Kimmy W. Chan & Caleb H. Tse, Assessing Celebrity Endorsement in China: A Consumer-Celebrity Relational Approach, Journal of Advertising Research, Vol. 51, No. 4 (Dec. 2011), Advertising Research Foundation, http://www.journalofadvertisingresearch.com/content/51/4/608.full.pdf+html.

[ix] Mingqian Li, On Regulation of Celebrity Endorsement in China, Journal of Politics and Law, Vol. 4, No. 1 (Mar. 2011), Canadian Center of Science and Education, http://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/jpl/article/view/9599/6891. For example, Guo Degang was reportedly paid 2 million yuan for endorsing a fake diet tea.

[x] Wu Jiayn, False endorsements by celebrities can put them into a pickle, Shanghai Daily (Mar. 23, 2009), http://www.shanghaidaily.com/Opinion/chinese-perspectives/False-endorsements-by-celebrities-can-put-them-into-a-pickle/shdaily.shtml.

[xi] Will China’s tough new ad laws impact beauty? Cosmetics Business (Jan. 20, 2016), http://www.cosmeticsbusiness.com/technical/article_page/Will_Chinas_tough_new_ad_laws_impact_beauty/114945.

[xii] Jiani Yan, Fonterra in the San Lu milk scandal: A Case Study of a New Zealand Company in a Product-harm Crisis, Lincoln University, https://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10182/4200/yan_bcom.pdf;sequence=3.

[xiii] Supra note 11.

[xiv] Chang Ping, Celebrity Spokespersons Cannot Just Claim Innocence, Southern Metropolis Daily (Sep. 20, 2008).

[xv] An Baijie, Stars could face penalty over food ads, China Daily (May 6, 2013), http://en.people.cn/90882/8233066.html.

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] Director Feng Xiaogang wins celebrity endorsement lawsuit, Danwei (Nov. 13, 2008), http://www.danwei.org/advertising_and_marketing/celebrity_endorsement_lawsuit.php.

[xviii] Id.

[xix] Qin Zhongwei, CCTV host admits role in phony commercial, China Daily (Nov. 9, 2009), http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cndy/2009-11/09/content_8930044.htm.

[xx] Watch your comments, celebrities, China Daily (Nov. 4, 2009), http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/cityguide/2009-11/04/content_8911904.htm.

[xxi] Guo Degang in trouble for Fake Product Advertisement, China.org.cn (Mar. 17, 2007), http://www.china.org.cn/english/entertainment/203318.htm.

[xxii] Crosstalk Star Faces Court Action over “Diet” Tea, Xinhua News Agency (Apr. 11, 2007), http://www.china.org.cn/english/culture/206877.htm.

[xxiii] Id.

[xxiv] China Cracks Down on Celebrity Endorsements, Red Luxury (Nov. 14, 2013), http://red-luxury.com/beauty/china-cracks-down-on-celebrity-endorsements.

[xxv] Angela Doland, In China, Will Male Celebs Stop Endorsing Sanitary Pads? Advertising Age (Sep. 4, 2014), http://adage.com/article/global-news/china-require-celebrities-test-products-plug/294805/.

[xxvi] Article 38 of the Advertisement Law of the People’s Republic of China.

[xxvii] Article 38, paragraph 1, of the Advertisement Law reads: “Where, in violation of the provisions of this Law, false advertisements have been published to cheat and mislead consumers, thus infringing upon the lawful rights and interests of consumers who have bought the commodity or accepted the service, the advertiser shall bear civil liabilities according to law; if an advertising agent or advertisement publisher, who knows clearly or ought to know that the advertisement is false, still designs, produces and publishes the advertisement, it shall bear joint and several liability according to law.”

[xxviii] Article 54 of the Food Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China states as follows: “Food advertisements shall provide truthful information, shall not include any false or exaggerated information, and shall not claim any disease prevention or treatment functions. Food safety regulatory agencies or institutions undertaking food inspection and testing, food industry associations, or customer associations shall not recommend food to customers through advertisements or in any other forms.”

[xxix] Article 55, Id: “Civil societies or other organizations or individuals who recommend a food to consumers in untruthful advertisements that has caused damages to the lawful rights and interests of the customers shall bear joint liabilities with the food producer and trader.”

[xxx] Article 5 of Judicial Interpretation No. 9 of 2009 (“Interpretations on Several Issues Regarding the Application of Law on Criminal Cases Concerning the Production and/or Sale of Fake and Substandard Drugs”), May 27, 2009.

[xxxi] Article 2 of the Advertisement Law of the People’s Republic of China (as amended on September 1, 2015) reads: “This Law applies to commercial advertising activities by commodity operators or service providers to directly or indirectly introduce the commodities or services that they promote through certain media and form in the territories of the People’s Republic of China. Advertiser in this Law shall mean natural person, legal person or other organization that designs, produces and publishes advertising on its own or by commissioning others to promote commodity or service. Advertising Operator in this Law shall mean natural person, legal person or other organization that is commissioned to provide advertising design, production and agent services. Advertising Publisher in this Law shall mean natural person, legal person or other organization that publishes advertising for advertiser or advertising operator that is commissioned by advertiser. Endorser in this Law shall mean natural person, legal person or other organization, other than the advertiser, that recommends and testifies for commodity or service in their own name or image.”

[xxxii] This provision reminds the episode occurred in 2015, when toothpaste brand Crest was fined 6 million yuan for running a TV commercial showing the Taiwanese celebrity Dee Hsu His-Di boasting that her shiny teeth were white after only one day of using Crest toothpaste. According to the Shanghai Administrator for Industry and Commerce, Crest exaggerated the whitening effect of its product by photoshopping the advertisement.

[xxxiii] Article 28, Id: “An advertising is a false one when it cheats or misleads consumers using false or misleading content. An advertising is a false one in any of the following cases: 1) The commodity or service does not exist; 2) Commodity performance, function, origin, usage, quality, specifications, ingredients/components, price, manufacturer, valid period, sales and awards, among others, or service items, provider, format, quality, price, sales and awards, among others, or promise related to the commodity or service, among others, does not match the actual situation and has a material influence on the purchase decision; 3) Using fictional, falsified, or unsubstantiated scientific research, statistics, survey, excerpt or quotation, as supporting material; 4) Fabricating efficacy of using the commodity or service; 5) Other situations in which false or misleading content is used to cheat or mislead consumers.”

[xxxiv] Article 18 of the Amended Law: “The following content is not allowed in advertising for functional food: (…); use Endorser to recommend or testify; (…)”

[xxxv] Article 16, Id: “The following content is not allowed in advertising for medical, pharmaceutical and medical devices: (…); using Endorser to recommend or testify; (…)”

[xxxvi] Article 15, Id: “No advertising is allowed for special drugs such as narcotic, psychotropic, medicinal toxic and radioactive drugs, pharmaceutical chemical substances that can be easily turned into toxins, and drugs, medical devices and therapy for treating addiction to drugs.”

[xxxvii] Article 22, Id: “It is prohibited to publish tobacco advertising in mass media, public place, means of public transport, or outdoors. It is prohibited to distribute any form of tobacco advertising to minors. It is prohibited to use advertising and public interest announcement for other commodity or service to promote tobacco product name, trademark, package, design and similar content.”

[xxxviii] Article 20, Id: “It is prohibited to publish advertising for infant milk products, drinks or other foods that claim to fully or partially substitute breast milk in mass media or public places.”

[xxxix] Article 38, Id: “When an Endorser recommends or testifies for a commodity or service in an advertising, he or she should refer to facts, comply with provisions of this Law and other laws and regulations, and should not recommend or testify for commodity or service that he or she has not used.”

[xl] Article 23, Id: “Advertising for alcohol should not contain the following content: 1) Seducing or enticing people to drink, or promote uncontrolled drinking; 2) Depiction of drinking behavior; 3) Showing driving vehicle, operating vessel, or piloting airplane, among others; 4) Explicitly or implicitly indicating drinking has the efficacy of mitigating tension and anxiety, or improving physical vitality, among others.”

[xli] Article 56, Id: “In case the false advertisement for a commodity or service that matters to the life and health of the consumers causes harm to the consumers, the Advertising Operator, Advertising Publisher and Endorser should bear joint liabilities with the Advertiser. In case a false advertisement for a commodity or service other than those described in the above paragraph causes detriment to the consumers, and the Advertising Operator, Advertising Publisher and Endorser knows or should know advertising is false but still designs, produces, acts as agent, publishes, or recommends or testifies for it, the Advertising Operator, Advertising Publisher and Endorser should bear joint liabilities with the Advertiser.”

[xlii] Article 62, Id: “If there is any of the following case for the Endorser, the industry and commerce administration department should confiscate the illegal income, and issue a fine ranging from one to two times of the illegal income.”

[xliii] Article 38, Id: “When an Endorser recommends or testifies for a commodity or service in an advertising, he or she should refer to facts, comply with provisions of this Law and other laws and regulations, and should not recommend or testify for commodity or service that he or she has not used.”

[xliv] Supra note 26.