Voluntary and simplified nutrition labels are more and more common all around the world. The general assumption is that mandatory nutritional labels, while displaying nutritional information in the most appropriate possible way, have become too complicated for the average consumer to understand, and this can ultimately frustrate their purpose to guide consumers to wise dietary choices.

So, more and more, in addition to the mandatory nutritional labeling, we see (usually – but not always – on the front of pack) colored or graphic icons that try to summarize the nutritional information. The World Health Organization expressly recommends this kind of tool on the front pack and Codex is currently working on guidelines for front-of-pack nutrition labeling.

Simplifying nutritional label is not a simple task, as nutritional balance is a very complex concept which needs to take into account a very high number of factors. In fact, worldwide we see many different approaches.

For example, in the EU, food nutrient profiles (i.e. some kind of nutritional evaluation of various food products) were supposed to be adopted by January 2009 by the EU Commission, as required by EU Reg 1924/2006. However, this deadline has not been met and these profiles have not been adopted (yet).

At the same time – still in the EU – we see a proliferation of “additional forms of expression and presentation” by single governments for nutritional information.

UK approved the Red, Amber and Green color coding, basically a voluntary kind of nutritional labeling that focuses on the declaration of “bad” nutrients and energy – in short, the greener on the label, the lower their intake, the healthier the choice. A score is given to each “bad” nutrient (and therefore not to the food product as a whole).

Perhaps the most successful systems so far is the Nutri-score, created and promoted by French Ministry of Health.

Differently from UK color coding system, Nutri-score (a TM registered in various countries) provides a score to the food through a combination of letters and colors, and not to its specific nutrients. Most processed foods and beverages are eligible for Nutri-score, with very few exceptions. Importantly, the score is determined based on both low presence of “bad” nutrients and foods (energy, saturated fats, sugar, salt), and high presence of good ones (fibers, proteins, fruits, vegetables).

Australia has a Health Star Rating system – which evaluates both the food product as a whole and its specific nutrients. Evaluation is based on “bad nutrients” and “good” ones.

We have then many other labels which are basically certification trademarks by private or non-governmental entities – this is the case for example of the Front-of-Pack Nutrition Labeling Initiative, the “Healthy Choice” logo by the Choices International Foundation or the American Heart Association logo.

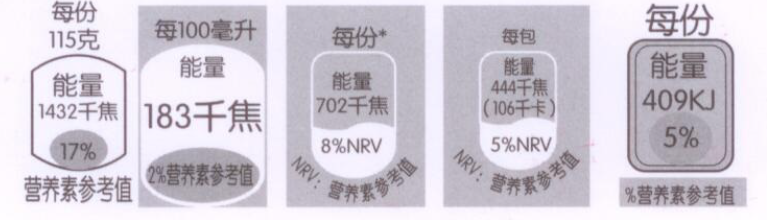

China is also moving in this direction. China National Food Industry Association (CNFIA), acknowledging that “iconic elements make it easier for consumers to read nutrition labels, this is a successful experience in the international market and in the food industries of developed countries”, has issued a Group Standard for “iconic simplification of the mandatory nutritional label”. It is a voluntary tool, aimed at explaining in a clearer way – from graphic point of view – the content of the mandatory nutritional labels which remain governed by GB 28050.

Beside this, China Nutrition Society has adopted in 2018 another specific Group Standard regulating the use of “Healthier choice” and “Smart choice” logos, with the purpose to clearly encourage consumers towards healthy products.

Use of the “Healthier choice” logo is encouraged in the last-circulated draft GB 28050, and it is thus likely to become an officially recommended/endorsed kind of voluntary labeling.

“Healthier choice” is overtly aimed at promoting reduction oil, sodium and sugar content in prepackaged foods, adjusting and optimizing product structure, boosting healthier food consumption. It is voluntary and applies only to specific food categories: cereal and grain products, bean products, dairy products, nuts and nut products, meat and meat products, aqua products, egg products, vegetable and fruit products. “Smart Choice” is also voluntary and can be used for beverages and other products (i.e. puffed products, gelatins, jelly and creamy products).

A food product can display the “Healthier choice” or the “Smart Choice” under the condition that it does not contain more than a specific amount of sugars, added sugars, saturated fats, fats. In this regard, the standard provides for a food classification, with specific thresholds for each food category.

“Healthier choice” or the “Smart Choice” are clearly inspired by the nutritional guidelines issued by China nutrition society in 2016 which stressed the importance to eat less high-salt and fried food (recommended daily salt intake ≤ 6g for adult, daily cooking oil 25-30g), as well as limiting daily intake of added sugar(not more than 50g, ideally less than 25g) as well as of trans fatty acid (under exceed 2g). In fact, excessive intake of these nutrients is related to higher risk for obesity and chronic diseases (also amongst children), hypertension, cerebral apoplexy and gastric cancer, coronary heart disease, dental problems.

“Healtier choice” and “Smart Choice” labeling on the other hand only focus on limiting intake of “bad” nutrients; it does promote or value the intake of “good” nutrients – such as fibers, vitamins, minerals, unsaturated fatty acids, proteins – or of foods with lower glycemic index, although the importance of these factors for achieving a healthy diet has been recognized by China nutrition Society in its 2016 guidelines.

Also, use of additives and sweeteners is not considered in the nutritional profile evaluation of the foods.

So far, both instruments seem not commonly used in the market.

Further research and worldwide harmonization will be very important to avoid that consumers receive conflicting information and are eventually mislead. Today, a same food may be a “healthier choice” in China but still bear “red flags” in the UK – for example instant noodles with 5-9 g/100g of saturated fatty acid content.