At some point in their studies, Chinese learners are bound to cross paths with Chinese four character idioms known as chengyu. Chinese idioms in the form of chengyu are an important part of learning Chinese, as they’re used regularly in both spoken and written Chinese expressions.

Chengyu have a long and significant history in Chinese culture. If you go to the library and read through some Chinese poetry, you’ll see that idioms are everywhere. If you watch Chinese TV, you’ll hear people spouting off chengyu like it’s nothing. If you try to learn Mandarin with Chinese songs, you’re bound to encounter chengyu in the lyrics.

When you put in the effort, a good mastery of Chinese idioms will help you understand Chinese culture, but it will also help you express yourself in an authentic way. In this article, we’re going to figure out what exactly a chengyu is and take a look at some of the most common Chinese idioms for you to grow your vocabulary.

Chinese Idioms: What Exactly Is a Chengyu (成语; chéngyǔ)?

Chinese idioms—or 成语 (chéngyǔ)—can be proverbs, common sayings, idiomatic phrases, or groups of words that convey a figurative meaning that goes beyond the words’ literal meanings. Most Chinese chengyu have been derived from ancient myths, stories, or historical facts.

While all 成语 are Chinese idioms that consist of four characters, not all Chinese idioms expressed in four characters are 成语.

What Makes a Chengyu?

There are a few tell-tale signs that help you pick out a chengyu:

- They consist of four characters.

- They are typically used as independent phrases.

- They don’t adhere to the usual SVO (subject, verb, object) syntax.

As chengyu are usually drawn from Chinese literature and history, it can be very difficult to understand what a specific chengyu means without understanding the context. Consequently, more so than memorizing Chinese idioms in English, learning Chinese idiom stories will help you better grasp their meanings while exposing you to interesting stories from Chinese cultural history.

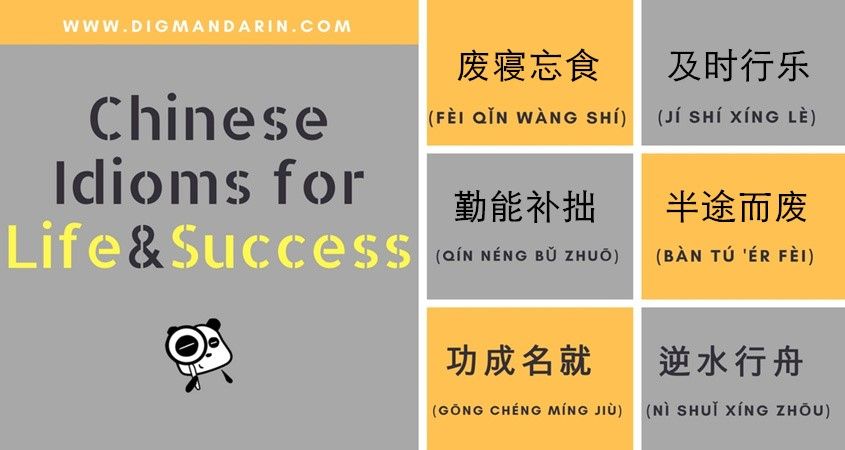

Chengyu List: Useful Chengyu to Learn

1. 马马虎虎 (mǎ ma hū hu)

马马虎虎 is a famous chengyu because its literal translation means “horse horse, tiger tiger.” This fun phrase most commonly means “so-so” or “not bad.” Nowadays, the idiom can also refer to the carelessness of people or the ordinariness of situations and things.

Example 1:

Chinese: 我妹妹是个马马虎虎的人,经常丢三落四。

Pinyin: Wǒ mèimei shì ge mǎma hūhu de rén, jīngcháng diūsānlàsì.

English: My sister is a careless person and always forgets about things.

Example 2:

Chinese:

- 你唱歌好听吗?

- 马马虎虎

Pinyin:

- Nǐ chàng gē hǎo tīng ma?

- Mǎma hūhu.

English:

- Are you a good singer?

- Just so-so.

What’s the Story Behind 马马虎虎?

Here’s the story from eChineseLearning:

In the Song Dynasty, there was once a man who painted whatever he felt like. One day, a friend asked him to paint a horse for him.

Having recently finished painting a tiger’s head, the painter simply added a horse’s body to the head he had already painted.

When the friend asked whether the image was of a tiger of a horse, the man bluntly responded: “马马虎虎” (mǎma hūhu; horse and tiger).

2. 熟能生巧 (shú nénɡ shēnɡ qiǎo)

熟能生巧 is a Chinese saying that tells us that skills come from practice. Think of this one as meaning something like “practice makes perfect” or “you’ll get the hang of it soon enough.”

Example:

Chinese: 写汉字要多练习,才可以熟能生巧。

Pinyin: Xiě hànzì yào duō liànxí, cái kéyǐ shúnénɡshēnɡqiǎo

English: It takes a lot of practice to write Chinese characters well.

What’s the Story Behind 熟能生巧?

There was once a very talented archer by the name of Chen Yaozi who lived during the Song Dynasty. He was so skillful at hitting targets that he earned the nickname “The Magic Archer.” One day, as Chen Yaozi was practicing—and hitting the target nearly every time—an old man selling oil stood to watch him for a while.

Feeling proud of his skills, Chen Yaozi asked the old man if he knew anything about archery himself. The old man dismissively replied that Chen Yaozi’s archery skills were nothing, as all it took was constant practice. Infuriated, Chen Yaozi demanded, “How dare you underestimate my skill?”

Saying nothing, the old man took out a bottlenecked gourd and placed it on the floor. He placed a coin with a hole in the middle on top of the gourd. Then, using a ladle, the old man poured oil into the gourd without spilling a drop of oil onto the coin. The old man turned around and told Chen Yaozi that his skillful oil pouring was also nothing—it was only a matter of repetition.

3. 九牛一毛 (jiǔ niú yì máo)

This idiom literally translates to “one hair from nine oxen.” This chengyu is used to describe something that is relatively small and insignificant when compared to a bigger picture, like one hair taken from a group of nine cows. An English idiom that’s similar to this chengyu is “a drop in the bucket.”

Example:

Chinese: 在7000万只狗里,受感染的数量不过是九牛一毛而已

Pinyin: Zài 7000 wànzhǐ gǒu lǐ, shòu gǎnrǎn de shùliàng bú guò shì jiǔniúyìmáo éryǐ

English: In a population of 70 million, that’s a drop in the bucket.

What’s the Story Behind 九牛一毛?

Here’s the story from Learning Mandarin Chinese:

Under the rule of Emperor Wu of Han, Li Ling, a great general, was forced to surrender in battle, though he had another plan in mind. As a result, rumors began to circulate around the emperor that Li Ling’s surrender was a failure.

Trying to advise the emperor that Li Ling must have surrendered for a good reason, Sima Qian defended Li Ling. The emperor grew angry and imprisoned Sima Qian.

In a letter to a friend, Sima Qian then wrote:

“I’m currently working on a book of history. If I end up dying here, it would only be as if one ox in a group of nine were to lose a single hair or as if one ant were to die. Punishment will not deter me from finishing this book.”

In the end, Sima Qian was able to complete his magnum opus, the Records of the Grand Historian (史记; Shǐjì).

4. 家喻户晓 (jiā yù hù xiǎo)

In English, this idiom means something like “well known” or “understood by everyone.”

Example:

Chinese: 這是一個家喻戶曉的故事。

Pinyin: zhè shì yí gè jiā yù hù xiǎo de gù shi.

English: It’s a story known to every household.

What’s the Story Behind 家喻户晓?

Here’s the story from Transparent Language:

The origin story of this chengyu centers around a woman named Liang. Once, after she had left the house, her house caught on fire. Upon returning home and seeing the flames, she realized that her nephew as well as her own child were still inside the burning house. Liang then ran into the house. She hoped to rescue her nephew first.

When Liang emerged from the smoke, she found that she had actually rescued her own child. She feared that others would criticize her for being selfish, so she ran back into the house to save her nephew as well. Unfortunately, she didn’t make it back out alive.

Following this tragedy, everyone in the village was aware of Liang’s story and fate.

5. 买椟还珠 (mǎi dú huán zhū)

买椟还珠 literally means “keep the case and return the pearl.” Figuratively, the idiom means “to show poor judgment.”

Example:

Situation: Your friend buys a nice phone that comes with a protective case. They throw away the phone but keep the case. Upon learning this, you’d say:

Chinese: 你这是买椟还珠。

Pinyin: nǐ zhè shì mǎi dú huán zhū.

English: You’re buying the case and returning the pearl.

What’s the Story Behind 买椟还珠?

The story behind this chengyu takes place in the Chu State. Once there was a merchant selling a valuable pearl. To showcase the gem and mark up its price, he put the pearl in an elaborate case.

When a man from the Zheng State came across the pearl, he was struck by its beauty. He ended up buying it from the merchant.

However, just minutes later, the customer returned to the merchant to return the pearl.

The merchant was surprised. It turned out that the merchant knew how to sell the elaborate case but not the pearl, while the customer had no idea how to gauge the values of the pearl and its container.

More Chinese Idioms to Use in Everyday Conversations

- 入乡随俗 (rù xiāng suí sú): This means something like “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” When you visit somewhere new, you should pick up the local customs.

- 一模一样 (yì mú yí yàng): This is close to the expression “two peas in a pod.” It is used to describe things that are exactly the same.

- 一见钟情 (yí jiàn zhōng qíng): This idiom means “to fall in love at first sight.” This can express affection for people as well as physical objects. If you want to tell someone you love them in plain language, you can just say “我爱你!” (wǒ ài nǐ!).

- 乱七八糟 (luàn qī bā zāo): This translates to “a total mess.” This chengyu can describe anything messy, from a disorganized office, to an inept bureaucracy, to a confusing personal relationship.

- 半途而废 (bàn tú ér fèi): This refers to starting an endeavor only to quit midway through. The chengyu literally means “to walk half the road and give up.”

- 亡羊补牢 (wáng yáng bǔ láo): The literal meaning of this chengyu is “to repair the pen after the sheep is dead.” Figuratively, it means something like “to act belatedly” or the English idiom “better late than never.”

- 感恩戴德 (gǎn ēn dài dé): This idiom refers to a heart overflowing with thankfulness, and it’s used to express great gratitude. To express thanks in plain language, you can say “谢谢你!” (xiè xiè nǐ!).

Conclusion

Learning and memorizing some of the most frequently used Chinese idioms will greatly improve your speech in Mandarin. Knowing how and when to use these idioms can earn you the respect of your Chinese-speaking friends and colleagues, particularly if you also know the Chinese chengyu stories behind them.

Hack Chinese, an app designed to help students learn Chinese vocabulary, can also help you memorize chengyu. Hack Chinese allows you to make your own vocabulary lists and add new or unknown words and phrases to them. Once you add the chengyu you want to learn to a list, you can practice them on a daily basis. After all, 熟能生巧 (shú nénɡ shēnɡ qiǎo; practice makes perfect)!